In the late summer of 1975 a small throng of astronomers and physicists, plus hangers-on thereof, gathered at Tuolumne Meadows on the western side of Yosemite National Park. I came along, as a wet-behind-the-ears grad student. The official reason was the "Sierra Conference on Astrophysics", where scientists from various universities and institutes could share news of their research. The true motivation, however, was far more important: to camp outdoors, to hike the mountains, and to experience for a few days the infinite reality of Nature.

A group of us decided one afternoon to scramble up Mount Dana. We went in shorts and t-shirts and tennis shoes, thoroughly unprepared. (I brought a thin nylon windbreaker. Give me a bonus point.) John Muir described what we saw (The Century Magazine, Vol. XL, No. 5, September, 1890):

The excursion to the top of Mount Dana is a very easy one; for though the mountain is 13,000 feet high, the ascent from the west side is so gentle and smooth that one may ride a mule to the very summit. Across many a busy stream, from meadow to meadow, lies your flowery way, the views all sublime; and they are seldom hidden by irregular foregrounds. As you gradually ascend, new mountains come into sight, enriching the landscape; peak rising above peak with its individual architecture, and its masses of fountain snow in endless variety of position and light and shade. Now your attention is turned to the moraines, sweeping in beautiful curves from the hollows and cañons of the mountains, regular in form as railroad embankments, or to the glossy waves and pavements of granite rising here and there from the flowery sod, polished a thousand years ago and still shining. Towards the base of the mountain you note the dwarfing of the trees, until at a height of about 11,000 feet you find patches of the tough white-barked pine pressed so flat by the ten or twenty feet of snow piled upon them every winter for centuries that you may walk over them as if walking on a shaggy rug. And, if curious about such things, you may discover specimens of this hardy mountaineer of a tree, not more than four feet high and about as many inches in diameter at the ground, that are from two hundred to four hundred years old, and are still holding on bravely to life, making the most of their short summers, shaking their tasseled needles in the breeze right cheerily, drinking the thin sunshine, and maturing their fine purple cones as if they meant to live forever. The general view from the summit is one of the most extensive and sublime to be found in all the range. To the eastward you gaze far out over the hot desert plains and mountains of the "Great Basin," range beyond range extending with soft outlines blue and purple in the distance. More than six thousand feet below you lies Lake Mono, overshadowed by the mountain on which you stand. It is ten miles in diameter from north to south and fourteen from east to west, but appears nearly circular, lying bare in the treeless desert like a disk of burnished metal, though at times it is swept by storm-winds from the mountains and streaked with foam. To the south of the lake there is a range of pale-gray volcanoes, now extinct, and though the highest of them rise nearly two thousand feet above the lake, you can look down into their well-defined circular, cup-like craters, from which, a comparatively short time ago, ashes and cinders were showered over the surrounding plains and glacier-laden mountains.

To the westward the landscape is made up of gray glaciated rocks and ridges, separated by a labyrinth of cañons and darkened with lines and broad fields of forest, while small lakes and meadows dot the foreground. Northward and southward the jagged peaks and towers that are marshaled along the axis of the range are seen in all their glory, crowded together in some places like trees in groves, making landscapes of wild, extravagant, bewildering magnificence, yet calm and silent as the scenery of the sky.

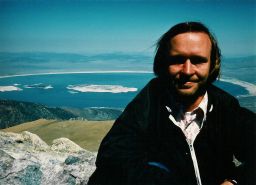

All of that we experienced. A comrade (probably Carl Caves) snapped a photograph of me at the summit of Mount Dana, with Mono Lake in the background. (Yep, that's me, in my pre-beard youth. Click on the thumbnail image to get a higher-resolution version.) During the past quarter-century most of the lake has dried up, as the water that formerly fed it was diverted to California cities.

After breathing the High Sierra air for a while some of us noticed the time. Instead of returning the way we had come, however, we decided to see new landscapes and take a "short cut" via the eastern side of the mountain. Duh! It was the classic hiking blunder, committed by a bunch of people who should have known better. As the shadows lengthened and the sky darkened, we stumbled downslope — and became more and more worried. By luck rather than by good navigation (in those pre-GPS days) we reached the main road at Tioga Pass just as night fell. Whew!

We learned something from that experience — just as we learned from the lectures and presentations on astrophysical research in the evenings. As John Muir wrote, "When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe." Yep ... but we usually don't notice.

(see also LivingPhilosophy (12 Jun 1999), CollegeCollage3 (29 Sep 2001), BeneathNotice (23 May 2003), ... )

TopicPersonalHistory - TopicArt - TopicRecreation - TopicScience - 2004-09-03

(correlates: Comments on RebelliousHair, EasternYosemiteMountains, ArtfulQuotes, ...)