Howdy, pilgrim! You're in volume 0.41 of the ^zhurnal — see ZhurnalyWiki on zhurnaly.com for a parallel "live" Wiki edition; see Zhurnal and Zhurnaly for quick clues as to what this is all about. (Briefly: it's the journal of ^z = Mark Zimmermann ... previous volume = 0.40 ... complete list at bottom of page ... send comments & suggestions to "z (at) his (dot) com" ... tnx!)

There are things we won't do.

There are things we shouldn't do.

But there are no things we can't do!

(see also Mission Statement (2 Nov 2001), ...)

- Sunday, September 26, 2004 at 17:04:04 (EDT)

By the early 1970s Fred Hoyle was already somewhat of a celebrity. He was an inventive and engaging astronomer who had written a science-fiction novel and had garnered considerable press coverage of his Steady State theory of the cosmos.

Quick context: the Copernican Principle says that the Earth isn't in a special location relative to everything else. Extending that, the Cosmological Principle argues that the universe looks the same in all directions (averaging out clusters of galaxies). Hoyle postulated a Perfect Cosmological Principle: not only are we not in a special place, we're also not in a special time --- so everything should look pretty much the same regardless of both where and when one is living. In order to keep things from thinning out as the universe expands, a Steady State demands continuous creation of matter.

Steady State cosmology is in many ways philosophically attractive, and I enjoyed believing in it during my teenage years. Alas, a multiplicity of observations (red-shift measurements of light from distant galaxies, ages of stars and star clusters, black-body microwave radiation, the abundances of various elements, ...) all suggest strongly that the universe had a hot, dense origin ~15 billion years ago --- the "Big Bang", to use a term coined by Hoyle himself in sarcastic reference to a theory he disagreed with.

Circa 1973 Fred Hoyle visited Rice University. I sat near the front row of the lecture hall and caught him in a pensive moment. (I used available light, 8mm Tri-X film, and a subminiature Yashica Atoron camera. A print surfaced here recently; click on the above image for a higher resolution version.)

Sir Fred Hoyle (1915-2001) --- continuously creative, now in a steady state ...

(see also Cherished Beliefs (19 Apr 2000), Late Physicists (24 Sep 2000), College Collage 1 (29 Sep 2000), College Collage 2 (3 Oct 2000), Universal Knowns (13 Jun 2002), ... )

- Saturday, September 25, 2004 at 15:21:00 (EDT)

Last year, psychologists at the University of Michigan reported that when they asked subjects to perform two or more experimental tasks --- solving arithmetic problems, say, at the same time they identified a series of shapes --- the frontal cortex, the executive function center of the brain, had to switch constantly, toggling back and forth in a stutter that added as much as 50 percent to the time it would have taken to perform the tasks sequentially instead of simultaneously.

In another study, scientists at Carnegie Mellon put subjects in an M.R.I. machine and asked them to listen to complicated sentences at the same time that they mentally rotated geometric shapes. The two tasks activated different parts of the brain, but each region was operating at a suboptimal level. Here, then, was high-tech confirmation of the common-sense wisdom of Publilius Syrus, a Roman philosopher from the first century B.C., who warned, "To do two things at once is to do neither." (Publilius also came up with "Better late than never" and "A rolling stone gathers no moss.")

It's quality that suffers with timesharing --- and quality isn't easily measured, especially in thinking and in interpersonal relationships ...

(see also Triple Think (25 Jul 2002), ... )

- Friday, September 24, 2004 at 06:26:10 (EDT)

But how far is a verst? Turning to the Net of Lies and Occasional Truths, one finds that a verst (more properly Верста = versta) is a traditional Russian unit equal to 500 sazhen (сажень); a shazen in turn is 3 arshin (аршин). And finally the light dawns: an arshin is defined as 28 English inches. So a sazhen converts to 7 feet, and a verst comes to about two-thirds of a mile (~1.07 km). Now I can get back to those forced marches, pursued by Napoleon ...

(see also Creative Devices (1 Jan 2001), Truth In Battle (11 Feb 2001), Ragged Runner (23 Mar 2002), ... )

- Wednesday, September 22, 2004 at 17:54:26 (EDT)

The same pulse-pounding emotional appreciation of fine workmanship came to me again years later in 1974, when I got my first 35mm single-lens reflex camera, a Canon TX-1. Likewise in 1984, as I unpacked a 128k Apple Macintosh computer. And most recently, experiencing Paulette's MINI Cooper automobile. Elegant engineering, delightful design, immaculate implementation. That's craftsmanship.

So I can forgive Gina Kolata when she rhapsodizes about her new bicycle (in "Fast Pace, Hard Seat: Now That's Cycling", New York Times, 6 Jul 2004):

The dimpled young man at the shop was crestfallen when I grabbed the bicycle and dashed out. He wanted me to ride it around the parking lot.

"Why?" I asked.

"I wanted to see the expression on your face," he explained.

I scoffed. After all, this was just a bicycle, I thought. The difference is it will fit me. The pain in the back of my neck will no longer plague me and I will do better on hills.

When I got home, my son and I headed out for a quick ride. Before I had gone a quarter-mile, I knew what the man at the shop meant. The bicycle responded, it handled, it moved, it was like a living thing. I was flying. Now that was bicycling.

And I also forgive Ms. Kolata her biker-chauvinism, when she suggests that cycling is the superior form of exercise. She suggests that "... runners rarely run for an hour and bicyclists rarely ride for less than an hour." Au contraire! I think it's scarcely worth tying on the stinky sneakers for a jog of under 90 minutes duration, and I've got a lot of company on the trails. LSD --- Long Slow Distance --- is a thriving religion.

I will concede that runners get injured; I've been fortunate on that front for many months, thank goodness. But how about all the cyclists that I pass, stopped to fix a flat tire or reinstall a derailed chain? Not to mention the catastrophic crashes that sometimes happen, particularly on dirt or gravel? OK, I guess I also have a Face Plant (9 Aug 2004) to report. In terms of calories burnt per unit of time, though, for a normal person there's no question that run trumps ride. And don't forget the cost of a fancy velocipede nowadays. Running shoes, in contrast, seem almost free, and they're the priciest part of a jog.

Probably I'll join Gina's team in a few years, when the old knees (and ankles, and hips) give out. Meanwhile I plan to keep pounding the pavement --- even though my puny physique can't compete with the sexy curves of a new high-tech bike.

Hmmm ... maybe if I start lifting weights ...

(see also Elegant Technologies (10 Sep 1999), Ultra Man (8 May 2002), High Precision (16 Jul 2002), Big Bad Boxes (3 Dec 2002), More Elegant Technologies (8 Nov 2003), ... )

- Tuesday, September 21, 2004 at 04:06:28 (EDT)

First we thought the PC was a calculator. Then we found out how to turn numbers into letters with ASCII --- and we thought it was a typewriter. Then we discovered graphics, and we thought it was a television. With the World Wide Web, we've realized it's a brochure.

... and maybe now it's a soapbox ...

(quote spotted on one of Jonathan Sturm's Ephimerides [1] pages; see also Something To Sell (14 Apr 2002), This Space For (17 Feb 2003),For Themselves (8 Jun 2003), Max Headroom (11 Sep 2003), ... )

- Monday, September 20, 2004 at 06:38:41 (EDT)

Consider all the possible ways for a beam of light to get from one point to another. Which one takes the least time? If the space between start and endpoint is empty, the answer is simply a straight line --- and that's the route the light takes. But what if there's a wall of clear glass set between the origin and the destination? The speed of light is slower within glass, so the winning least-time path will bend to reduce the amount of glass that the light has to go through. That zig-zag makes the total path length outside the glass a bit longer. There's a trade-off determined by the relative speed inside and outside, which is precisely what "Snell's Law" predicts with its tricky trigonometric functions of "index of refraction". That's the Least Time Principle.

Particles --- like electrons, or bowling balls, or planets --- move from Point A to Point B not to minimize time, but to minimize something else, a funny combination of kinetic and potential energy called the Lagrangian. Add up ("integrate") the value of the Lagrangian at every point along the path and find the route that makes the answer as small as possible. That's the classical pathway that the particle will follow.

Why in the world does this work? There are two answers, one formal and one physical:

Why call the second explanation "physical"? Because it's not merely a trick --- all particles are, at a deep level of reality, governed by quantum-mechanical laws that describe them in terms of tiny vibrations (aka the Schrödinger Wave Equation). And light is even more so: it's made of electromagnetic waves that naturally interfere with one another, bend around obstacles, and bounce off barriers.

Or perhaps not. For many practical purposes it's a lot easier to let particles be particles, and to treat light as rays that fly merrily along. One of my first personal-computational-recreational projects, when I got my hands on a programmable calculator with an attached X-Y plotter ca. 1975, was to write simple programs to trace rays of light through various lenses and media. (Yeah, I was a strange bird. And maybe "was" is the wrong verb tense, eh?!)

I had such fun listening to the stepper-motors whirr and watching the little felt-tip pen kachunk kachunk across the paper, drawing a line along the path that the imitation light followed. I put simulated lenses together to make simulated telescopes. I experimented algorithmically with retroreflective road-sign material: little beads that catch and carom photons back toward the direction that they came from.

And I also played in the conjugate domain, adding up little navies of waves and seeing how they interfered, constructively or destructively. I remember watching the plotter pen spiral, around and around toward the center of the page, as it summed wiggly terms for me near a zero of the Riemmann zeta function ...

(see also Fringe Of Things (25 Jun 1999), Coherent Interference (28 Dec 1999), College Collage 3 (29 Sep 2001), Personal Programming History (2 Apr 2002), Fractal Feynman (30 Jan 2003), Combinatorial Interference (10 Sep 2003), Prime Obsession (4 Jan 2004), Brewster Angle (19 Feb 2004), ... )

- Saturday, September 18, 2004 at 09:40:42 (EDT)

A couple of months ago Alex Williams wrote about "oppies", aka organic professionals, in "Going Up the Country, but Keeping All Your Toys" (18 Jul 2004 New York Times). The article wasn't ostensibly meant to be ironic, but it definitely read that way from my perspective. More recently, in an op-ed essay a writer (who shall mercifully remain nameless here) wrung her hands about how much more time her tiny daughters spent with the nanny than with her --- but how, as they start attending daycare, the Quality Time equation will shift in Mommy's favor. Not a thought given to working fewer hours, earning less money, and having more time for her family. Not an allusion made to the vast majority who can't afford nannies, or decent child care at all for that matter. And to add further spice: the writer's byline reveals that she's on the staff of a small asteroid in the Time Inc. conglomerate-corporate universe, Real Simple, which purports to be "the magazine about simplifying your life".

But look at the web site and it's really about buying stuff. Check out the Privacy Policy, and it's really about selling names. And the advertisements in the on-paper 'zine? Strange how the pursuit of simplicity always involves spending more money ...

(see also Something To Sell (14 Apr 2002), More Fun Less Stuff (1 Oct 2002), For Themselves (8 Jun 2003), Cut The Volume (5 Mar 2004), Dalai Lama Birthday Gift (24 Aug 2004), ... )

- Friday, September 17, 2004 at 05:38:52 (EDT)

And there's also the abandoned/converted rail line:

(for maps and other information see [1], [2], [3], and [4]; see also Rock Creek Trail (31 May 2002), Healthy Trails (24 Nov 2002), Anacostia Tributaries (28 Jan 2003), Capital Crescent Coordinates (5 May 2003), Loop Course (24 Aug 2003), Ten League Ley Lines (23 Nov 2003), ... )

- Wednesday, September 15, 2004 at 21:09:12 (EDT)

"You are good in every way, Andrei, but you have a kind of pride of intellect," said the Princess, following her own train of thought rather than the conversation, "and that is a great sin."

The phrase "pride of intellect" resonated as I read "The Wilderness Campaign", a profile of former US Vice President Al Gore (by David Remnick in The New Yorker[1], 13 Sep 2004). Gore is analytic, articulate, and hyperacidic as he muses about recent events. His comments about the current Administration are fascinating, both in their content and in what they reveal about Gore himself:

"I wasn't surprised by Bush's economic policies, but I was surprised by the foreign policy, and I think he was, too," Gore told me. "The real distinction of this Presidency is that, at its core, he is a very weak man. He projects himself as incredibly strong, but behind closed doors he is incapable of saying no to his biggest financial supporters and his coalition in the Oval Office. He's been shockingly malleable to Cheney and Rumsfeld and Wolfowitz and the whole New American Century bunch. He was rolled in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. He was too weak to resist it.

"I'm not of the school that questions his intelligence," Gore went on. "There are different kinds of intelligence, and it's arrogant for a person with one kind of intelligence to question someone with another kind. He certainly is a master at some things, and he has a following. He seeks strength in simplicity. But, in today's world, that's often a problem. I don't think that he's weak intellectually. I think that he is incurious. It's astonishing to me that he'd spend an hour with his incoming Secretary of the Treasury and not ask him a single question. But I think his weakness is a moral weakness. I think he is a bully, and, like all bullies, he's a coward when confronted with a force that he's fearful of. His reaction to the extravagant and unbelievably selfish wish list of the wealthy interest groups that put him in the White House is obsequious. The degree of obsequiousness that is involved in saying 'yes, yes, yes, yes, yes' to whatever these people want, no matter the damage and harm done to the nation as a wholeóthat can come only from genuine moral cowardice. I don't see any other explanation for it, because it's not a question of principle. The only common denominator is each of the groups has a lot of money that they're willing to put in service to his political fortunes and their ferocious and unyielding pursuit of public policies that benefit them at the expense of the nation."

An extraordinarily nuanced critique. True? Perhaps, in part. Fair? Some might argue that both major parties have prostituted themselves to big money and powerful interest groups. (That doesn't make it right!) Al Gore himself was once a mega-fundraiser, tiptoeing along the edge of the illicit, memorable still for his mantra "... no controlling legal authority ..." in response to criticism.

Pride of intellect --- undeniable, in spite of an explicit disavowal. But on the happy side, there are signs that Al Gore is coming back to humanity after too many years in politics. As he repeatedly zen-jokes, "You win some, you lose some --- and then thereís that little-known third category."

(see also Weight Of Office (30 Nov 2000), Make Money Whisper (9 Nov 2002), , Campaign Reform (30 Dec 2003), Age Weighted Voting (20 Feb 2004), ... )

- Tuesday, September 14, 2004 at 05:27:19 (EDT)

pooportunity

Its definition? Maybe "a chance to take advantage of bad circumstances". Or perhaps, more crudely but sometimes more importantly, "the possibility of going to the loo".

And that thought apropos the knock of opportunity (the word my comrade was actually trying to type) reminds me of the answer that Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, reputedly gave to reporters who asked him what great lesson he had learned from his long experience in warfare:

P*ss when you can!

(see also Self Absorption (27 Mar 2003), ... )

- Monday, September 13, 2004 at 05:31:31 (EDT)

Each number will be furnished with from two to five original Engravings, many of them elegant, and illustrative of New Inventions, Scientific Principles, and Curious Works; and will contain, in addition to the most interesting news of passing events, general notices of progress of Mechanical and other Scientific Improvements; American and Foreign. Improvements and Inventions; Catalogues of American Patents; Scientific Essays, illustrative of the principles of the sciences of Mechanics, Chemistry, and Architecture: useful information and instruction in various Arts and Trades; Curious Philosophical Experiments; Miscellaneous Intelligence, Music and Poetry.

This paper is especially entitled to the patronage of Mechanics and Manufactures, being the only paper in America, devoted to the interest of those classes; but is particularly useful to farmers, as it will not only appraise them of improvements in agriculture implements, But instruct them in various mechanical trades, and guard them against impositions As a family newspaper, it will convey more useful intelligence to children and young people, than five times is cost in school instruction. Another important argument in favor of this paper, is that it will be worth two dollars at the end of the year when the volume is complete (old volumes of the New York Mechanic, being now worth double the original cost, in cash.)

There's a fascinating archive of early issues at the University of Rochester [1]. For its first century the magazine mainly offered news of invention and technology. But "science"? Not much. Long-term importance? Rather limited. Scientific American was quite a useful guide for inventors who sought new patents and for businessmen who wanted to market exciting gadgets. But it didn't change many lives.

In 1947, however, when Gerard Piel and friends bought Sci. Am. an amazing event happened. The magazine mutated into an extraordinary creature: a white-hot glowing focal point for ideas. Real working scientists wrote about their research, in language that was precise, detailed, yet accessible to a wide audience. The articles were heavy going in many cases. But along with their factual content they always conveyed the spirit of discovery, the thrill of learning something new, the joy of understanding Nature.

Back in the 1970s somebody joked that Scientific American had 700,000 subscribers and 700 readers. Maybe so. But among those 700 were young people who grew up to do incredible things on the frontiers of knowledge. Martin Gardner's "Mathematical Games" columns struck sparks in the darkness; so did countless other pieces. Some of those sparks started fires that still burn.

Scientific American is the oldest continuously-published magazine in the United States. It changed owners again in 1986 when it was sold to Verlagsgruppe Georg von Holtzbrinck. (I remember jesting at the time that it would soon be renamed Scientific German.) The 'zine has continued to evolve and nowadays has a far larger circulation plus editions in many languages, as well as an entertaining web site [2]. The articles are shorter and easier to read. The illustrations are bigger and more dramatic. A larger fraction of the material involves sci-gossip and techno-buzz. Profits are no doubt higher. But most of the magic is gone; perhaps it will return some day. Meanwhile, my subscription has lapsed.

Gerard Piel died last week. His academic training was in history, and he worked mainly as an editor and a publisher. He and his colleagues probably did more than anyone (with the possible exception of Isaac Asimov) to catalyze the increase and diffusion of human knowledge during the past 50 years.

Gerard Piel: Scientific Man

R.I.P. --- 1915-2004

(see also Meet Mind (19 Jul 1999), Fan Letter Feedback (7 Mar 2001), Jon Mathews (25 Apr 1999), Fractal Feynman (30 Jan 2003), Mind Children (17 Apr 2003), Thank You Bell Labs (26 May 2003), Club Science (26 Oct 2003), Explorers Club (12 Jun 2004), ... )

- Saturday, September 11, 2004 at 17:05:45 (EDT)

It's all about the difference between training and learning ...

(see also Pull Push (27 Mar 2001), Pursuit Of Excellence (22 Feb 2002), Parting Advice (21 Jun 2002), Liberal Arts (13 Mar 2003), Plural Of Virus (28 Aug 2004), ... )

- Thursday, September 09, 2004 at 17:25:38 (EDT)

"Honor, integrity, continually seeking knowledge and having fun are the values Red Robin Restaurants aspire to each day."

Not a bad set of goals ...

(see http://html.redrobin.com/Values.html ... see also Pick Two Out Of Three (5 Jun 1999), My Religion (6 Nov 2000), ... )

- Wednesday, September 08, 2004 at 06:19:45 (EDT)

Professor Brown begins with Nine 'Laws' of Ecological Bloodymindedness:

The First Law For every action on a complex dynamic system, there are unintended and unexpected consequences. In general, the unintended consequences are recognised later than those that are intended.

The Second Law Any system in a state of positive feedback will destroy itself unless a limit is placed on the flow of energy through that system.

The Third Law Any sedentary community, by virtue of its sedentism, will encounter problems of sanitation. The manner in which sanitation is managed will affect the manner in which supporting agriculture is managed.

The Fourth Law For every increment in the agricultural surplus there is a corresponding increment in the volume of urban sewage.

The Fifth Law Stability or resilience in ecosystems requires that all essential reactions within the system function within ranges of rates that are mutually compatible.

The Sixth Law The long-term survival of any species of organism requires that all processes essential for the viability of that species function at rates that are compatible with the overall functioning of the ecosystem of which that species is a part.

The Seventh Law If any species of animal should develop the mental and physical capacity consciously to manage the ecosystem of which it is a part, and proceeds to do so, then the long-term survival of that species will require, as a minimum, that it understands the rate limits of all processes essential to the functioning of that ecosystem and that it operates within those limits.

The Eighth Law Long-term stability or Ďsustainabilityí in ecosystems (including agricultural systems) is dependent in part upon the recycling of nutrient elements wholly within the system or upon their replenishment from a renewable source, provided such replenishment is not itself dependent upon a finite source of energy.

The Ninth Law If a population continues to grow exponentially it will eventually consume essential resources faster than they can be replenished. The provision of or access to additional resources will extend the Ďlifeí of such resources, and hence the duration of growth of the population, only to a very small extent.

As a sucker for lists, I've gotta like these (even though several of them deserve only to be corollaries or lemmas, not first-class "laws"). In Feed or Feedback Brown unfolds and explores the implications of his "laws". He summarizes the situation when he observes (Chapter 3):

In the course of human cultural evolution, societies were presented, if you like, with two questions. If they answered 'Yes' to Question 1, they proceeded to Question 2. If they answered 'No' to the first question, that was the end of it --- until, in the fullness of time, an answer was imposed by the descendants of those who had answered 'Yes' to both. The first question was, 'Do you want to convert from hunting and foraging to farming?'; the second was 'Do you want to build cities?' Those who answered 'Yes' to both grabbed the tail of the most implacable tiger the world has ever seen. ...

Marshalling his evidence, in impressive detail, takes Brown a few hundred pages. Then he concludes (Chapter 14):

The basis of my argument is this: we have succeeded in producing a system that, by some criteria, has worked very well for a limited period but cannot be 'sustained'. No matter what else we might do, there are two fundamental processes which, if allowed to continue, will certainly lead to the widespread destruction of our habitat, the collapse of civilisation(s), and perhaps the extinction of our species. If the last should happen it will be an impressive achievement --- to the best of my understanding, a world first. Plenty of other species have become extinct, usually because of changes in the physical environment and/or competition from or predation by other species. Extinction caused by a species, not only having the capacity consciously to modify the global environment so profoundly as to make it uninhabitable for itself, but actually going ahead and doing so, has all the essential ingredients of a particularly diabolical Irish joke.

The two basic processes to which I refer are: (1) The 'Vicious Circle', i.e. the positive feedback interaction between population and food supply, and (2) the use of some essential nutrient elements in a way that, for all practical purposes, is irreversible.

The first essential agricultural input to be depleted will probably be phosphate rock; Brown estimates that within 100-200 years its cost will skyrocket. Well before that time, however, Brown's analysis suggests that soil degradation, deforestation, depletion and pollution of water resources, and destruction of fisheries will result in widespread famine and death. It could happen abruptly, when reliance on a few species for food production results in a global ecosystem "... simplified to a level at which it becomes dangerously vulnerable to any of a number of types of stress --- both physical and biological." Or it could be a more gradual collapse, stretching for generations. Brown's best guess is that, if present trends continue, this will begin to be obvious by the middle of the 21st Century.

Prepare to tighten your belt ...

(see also Compassionate Carnivorism (19 Nov 2002), ... )

- Monday, September 06, 2004 at 09:01:56 (EDT)

But! What if there's an evolutionary advantage to having a blind spot? What if individuals who simply can't fathom some particular topic have a significant edge in the battle to get copies of their genes into the next generation? If so, then it's perfectly logical for some or all human beings, over the eons, to develop an utter inability to figure out that subject.

An example of such obscurity-by-darwinian-necessity? Consider the forever-fascinating riddle: the mind of the opposite sex. Might it not be helpful --- in order to bind couples together for years of joint child-rearing --- to ensure that one's partner always retains an element of mystery, an unpredictable core that continues to tantalize even after decades of observation? Could that ineluctable conundrum be part of what is called, for shorthand, "love"?

As always, the Bard says it best, in Antony and Cleopatra (II.ii.):

Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale Her infinite variety ...

And on that note, my male mind boggles. Honey, you can talk about it with your girlfriends for the rest of the day. I'm going out hunting ...

(see also The Mysterians (2 Aug 1999), Thoughtful Metaphors (8 Nov 2000), Man Of Mystery (12 Aug 2004), ... )

- Sunday, September 05, 2004 at 07:00:20 (EDT)

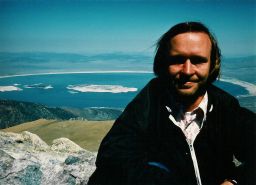

In the late summer of 1975 a small throng of astronomers and physicists, plus hangers-on thereof, gathered at Tuolumne Meadows on the western side of Yosemite National Park. I came along, as a wet-behind-the-ears grad student. The official reason was the "Sierra Conference on Astrophysics", where scientists from various universities and institutes could share news of their research. The true motivation, however, was far more important: to camp outdoors, to hike the mountains, and to experience for a few days the infinite reality of Nature.

A group of us decided one afternoon to scramble up Mount Dana. We went in shorts and t-shirts and tennis shoes, thoroughly unprepared. (I brought a thin nylon windbreaker. Give me a bonus point.) John Muir described what we saw (The Century Magazine, Vol. XL, No. 5, September, 1890):

The excursion to the top of Mount Dana is a very easy one; for though the mountain is 13,000 feet high, the ascent from the west side is so gentle and smooth that one may ride a mule to the very summit. Across many a busy stream, from meadow to meadow, lies your flowery way, the views all sublime; and they are seldom hidden by irregular foregrounds. As you gradually ascend, new mountains come into sight, enriching the landscape; peak rising above peak with its individual architecture, and its masses of fountain snow in endless variety of position and light and shade. Now your attention is turned to the moraines, sweeping in beautiful curves from the hollows and cañons of the mountains, regular in form as railroad embankments, or to the glossy waves and pavements of granite rising here and there from the flowery sod, polished a thousand years ago and still shining. Towards the base of the mountain you note the dwarfing of the trees, until at a height of about 11,000 feet you find patches of the tough white-barked pine pressed so flat by the ten or twenty feet of snow piled upon them every winter for centuries that you may walk over them as if walking on a shaggy rug. And, if curious about such things, you may discover specimens of this hardy mountaineer of a tree, not more than four feet high and about as many inches in diameter at the ground, that are from two hundred to four hundred years old, and are still holding on bravely to life, making the most of their short summers, shaking their tasseled needles in the breeze right cheerily, drinking the thin sunshine, and maturing their fine purple cones as if they meant to live forever. The general view from the summit is one of the most extensive and sublime to be found in all the range. To the eastward you gaze far out over the hot desert plains and mountains of the "Great Basin," range beyond range extending with soft outlines blue and purple in the distance. More than six thousand feet below you lies Lake Mono, overshadowed by the mountain on which you stand. It is ten miles in diameter from north to south and fourteen from east to west, but appears nearly circular, lying bare in the treeless desert like a disk of burnished metal, though at times it is swept by storm-winds from the mountains and streaked with foam. To the south of the lake there is a range of pale-gray volcanoes, now extinct, and though the highest of them rise nearly two thousand feet above the lake, you can look down into their well-defined circular, cup-like craters, from which, a comparatively short time ago, ashes and cinders were showered over the surrounding plains and glacier-laden mountains.

To the westward the landscape is made up of gray glaciated rocks and ridges, separated by a labyrinth of cañons and darkened with lines and broad fields of forest, while small lakes and meadows dot the foreground. Northward and southward the jagged peaks and towers that are marshaled along the axis of the range are seen in all their glory, crowded together in some places like trees in groves, making landscapes of wild, extravagant, bewildering magnificence, yet calm and silent as the scenery of the sky.

All of that we experienced. A comrade (probably Carl Caves) snapped a photograph of me at the summit of Mount Dana, with Mono Lake in the background. (Yep, that's me, in my pre-beard youth. Click on the thumbnail image to get a higher-resolution version.) During the past quarter-century most of the lake has dried up, as the water that formerly fed it was diverted to California cities.

After breathing the High Sierra air for a while some of us noticed the time. Instead of returning the way we had come, however, we decided to see new landscapes and take a "short cut" via the eastern side of the mountain. Duh! It was the classic hiking blunder, committed by a bunch of people who should have known better. As the shadows lengthened and the sky darkened, we stumbled downslope --- and became more and more worried. By luck rather than by good navigation (in those pre-GPS days) we reached the main road at Tioga Pass just as night fell. Whew!

We learned something from that experience --- just as we learned from the lectures and presentations on astrophysical research in the evenings. As John Muir wrote, "When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe." Yep ... but we usually don't notice.

(see also Living Philosophy (12 Jun 1999), College Collage 3 (29 Sep 2001), Beneath Notice (23 May 2003), ... )

- Friday, September 03, 2004 at 06:15:45 (EDT)

It doesnít matter what I say

So long as I sing with inflection

That makes you feel that Iíll convey

Some inner truth of vast reflection

But Iíve said nothing so far

And I can keep it up for as long as it takes

And it donít matter who you are

If Iím doing my job then itís your resolve that breaks

... and then the music cycles into the refrain --- following a chord progression from the ultimate musical hook of all time, Johann Pachelbel's "Canon in D" ...

(see also My Generation (2 Oct 2001), Lyric Notes (29 Mar 2002), Wonder Land (4 Jan 2003), ...)

- Thursday, September 02, 2004 at 05:51:59 (EDT)

Reading a book requires a degree of active attention and engagement. Indeed, reading itself is a progressive skill that depends on years of education and practice. By contrast, most electronic media such as television, recordings, and radio make fewer demands on their audiences, and indeed often require no more than passive participation. Even interactive electronic media, such as video games and the Internet, foster shorter attention spans and accelerated gratification.

While oral culture has a rich immediacy that is not to be dismissed, and electronic media offer the considerable advantages of diversity and access, print culture affords irreplaceable forms of focused attention and contemplation that make complex communications and insights possible. To lose such intellectual capability --- and the many sorts of human continuity it allows --- would constitute a vast cultural impoverishment.

When it came out "Reading at Risk" provoked significant, thoughtful commentary in the press. Andrew Soloman observed (in the New York Times, 10 July 2004):

... Kafka said, "A book must be an ice ax to break the seas frozen inside our soul." The metaphoric quality of writing --- the fact that so much can be expressed through the rearrangement of 26 shapes on a piece of paper --- is as exciting as the idea of a complete genetic code made up of four bases: man's work on a par with nature's. Discerning the patterns of those arrangements is the essence of civilization.

Solomon went on to diagnose the crisis in reading as a threat to national health and to political life. He concluded:

Reading is harder than watching television or playing video games. I think of the Epicurean mandate to exchange easier for more difficult pleasures, predicated on the understanding that those more difficult pleasures are more rewarding. I think of Walter Pater's declaration: "The service of philosophy, of speculative culture, towards the human spirit is to rouse, to startle it to a life of sharp and eager observation. . . . The poetic passion, the desire of beauty, the love of art for its own sake, has most; for art comes to you professing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass."

Michael Dirda (in the Washington Post, July 2004) commented that even the minority of people who still read aren't reading like they once did:

More and more, we have been straitjacketed and brainwashed by the books of the moment, the passing moment. Publishers know that they can promote almost any title to bestsellerdom. Glittery names and hot-button topics guarantee big sales, and so former presidents ... turn out their brick-like apologiae, even as aging Hollywood celebrities and rock divas produce glitzy children's picture books (no writing is harder to do well). And most of the nonfiction titles --- and half the fiction titles, too --- now seem to be about terrorism, homeland security or the ongoing crisis in the Middle East.

Dirda contrasted that with the mind-opening effect of worthwhile books and poems:

A true literary work is one that makes us see the world or ourselves in a new way. Most writers accomplish this through an imaginative and original use of language, which is why literature has been defined as writing that needs to be read (at least) twice. Great books tend to feel strange. They leave us uncomfortable. They make us turn their pages slowly. We are left shaken and stirred.

But who now is willing to put in the time or effort to read a real book? Most people expect printed matter to be easy. Too often, we expect the pages to aspire to the condition of television, and to just wash over us. But those who really care about literature nearly always sit down with a pencil in their hands, to underline, mark favorite passages, argue in the margins. The relationship between a book and reader may occasionally be likened to a love affair, but it's just as often a wrestling match. No pain, no gain.

This is why the NEA report shows that poetry is suffering most of all. Poets keep their language charged, they make severe demands on our attention, they cut us no slack. While most prose works the room like a smiling politician at a fundraiser, poetry stands quietly in the dusty street, as cool and self-contained as a lone gunfighter with his serape flapping in the wind. It's not glad-handing anybody.

And taking a look at "Reading at Risk" itself, there are some interesting statistical tidbits. The latest (2002) broad survey of readers in the US found:

In contrast to the dismal picture of reading trends are the findings on "creative writing" --- an activity which has actually grown over the past 20 years. An average of ~7% of the population compose stories, poems, or plays. Those with more education are somewhat likelier to write, as are those who are younger. But unlike the distribution of active readers, the chances of finding a writer are relatively independent of income and race. Perhaps the flame hasn't completely gone out yet ...

(see also On Booklessness (18 Jul 1999), Looming Disaster (6 Aug 2001), Improving My Mind (22 Jun 2003), Knowledge And Public Happiness (29 Jul 2003), Key To The Treasure (23 Apr 2004), ... )

- Wednesday, September 01, 2004 at 06:27:21 (EDT)

(14 Aug 2004) - 21+ miles, 240 minutes --- A cloudy, cool day as Hurricane (soon to be Tropical Storm) Charley approaches the area ... I get up at 4:30am, do the family laundry, and by 9:30 have readied myself to set out for an undefined but longish journey, fueled by 7-11 coffee and a lemon poppyseed Clif Bar. A 20 oz. Gatorade, quaffed 15 minutes before departure, provides good pre-hydration. From home I proceed via the Georgetown Branch trail to Rayís Meadow on Rock Creek Trail, which I follow northward to milepost 7 at Ken-Gar. Then itís backtrack along RCT to Cedar Lane and chat with a nice lady at the water fountain about her training strategy. Like me, she believes in relatively few but relatively long jogs (>1 hour each), at a sane pace. She has just finished a 9-miler, along a circuit similar to one of my old favorites involving RCT+CCT/GBT and Wisconsin Avenue.

The feetsies are still feeling good, so I vector west past NIH to Old Georgetown Road and south to Bethesda. Along the Capital Crescent Trail I visit mileposts 3.5-5.5, then reverse course to GBT marker 0.5 and thence home. Lots of other runners greet me (and pass me) on the trails, along with countless cyclists, pram-pushers, dog-walkers, and a few skaters.

My pace is deliberate, deliberately so. After ~9 miles I come up with a new theory: my optimal speed is slower by 1 minute/mile every time distance doubles. Thus if I can comfortably do a 5k at ~9 min/mi, for 10k my rate should be ~10 min/mi, for 20k it's ~11 min/mi, the marathon is ~12 min/mi, etc., etc. More details on this hypothesis another time.

Seven measured miles on RCT average 11:01 each. The penultimate seven along the CCT/GBT come in at 11:20 apiece. At about mile 20 it starts to drizzle and I suddenly feel tired; my final mile comes in at a tortoise-like 13:25. Probably I should have gone a few percent slower for the first half of the jaunt. (Or, since I usually get tired during the last mile no matter how far I'm going, maybe I just need to figure out a way to skip over that final distance, or fool myself into arriving home before I realize it?!) Consumed en route: ~64 oz. water + 1 crunchy peanutbutter Clif Bar.

(22 Aug 2004) - 17 miles, 192 minutes --- Venus shines like a brilliant-cut diamond as I leave home shortly before dawn. Sirius twinkles low in the southeast sky, presaging the flooding of the Nile (see Dog Star Rising). My hope is to walk the first mile but after five minutes my will weakens and I start jogging. In spite of further slow sauntering, mile 1 takes less than 13 minutes. A 20 oz. bottle of Gatorade lasts until downtown Bethesda.

I follow the Georgetown Branch / Capital Crescent Trail through the Dalecarlia Tunnel and arrive at Milepost 6.5 about 7:15am. A colleague training for her first marathon had tentatively planned to meet me there, but there's no sign of her. I do three out-and-back miles, nibbling on a lemon poppyseed Clif Bar as I ping-pong between mile markers 7 and 6. No comrade materializes by 7:50am, so I commence the return journey to Che^z. The slow start (first-half pace 11:30) leaves me with a good energy level and I blast (!) out the final four at 10:35/mile, including a top-speed 9:36 for mile 15.

(29 Aug) - 26+ miles, 362 minutes --- home to Lake Needwood and back, via Rock Creek Trail. I carry my wife's digital camera and take pictures of the mileposts along the way, for use on a web page eventually or to add eye candy to my Rock Creek Trail GPS coordinate collection. At 6am when I set out the temperature is ~73 F and the relative humidity is almost 100%; at noon as I return the thermometer climbs to ~85 F. Ugh!

A CSX freight train blocks the grade crossing a quarter mile from my house and delays me by ~5 minutes --- a fortunate early reminder to slow down. The 11 measured miles outbound along RCT average 13:32 (including time spent taking photos of mileposts and some bizarre orange "tree-ear" fungi growing on stumps); coming back the mean pace is 13:30 (including time spent changing socks and pouring water over my head at the fountains). I also photograph "Sue's Spot" near RCT Mile 11, the memorial garden for Sue Wen Stottmeister. (We should add something for the late Connie Barton there too. See SueWenRun, 29 May 2002)

I religiously walk up anything that resembles a hill, and do my best to go slowly, but it's tough to control the pace until near the end when my right foot begins hurting and I get a bit tired. Before starting I have a cup of coffee, a Clif bar, and 20 oz. of Gatorade. Along the way I nibble down ~2.5 Clif bars and drink ~50 oz. of water. I also carry another bottle of Gatorade for the first 7 miles and then hide it behind a tree; during the return trip I retrieve it and chug it.

Obvious lessons learned:

Overall, a successful experiment in long, slow jogging ... in spite of August heat and humidity. I spy huge numbers of cyclists and runners and walkers, one large deer, many squirrels, and one chipmunk.

Silly question: should this route be called the "Zimarathon", "Zimmarathon", or "Zimmermarathon"? (^_^)

(see also Robert Frost Trail (10 Aug 2004), ... )

- Tuesday, August 31, 2004 at 05:49:32 (EDT)

Regards,

the terse (but false):

Yours,

the insincere:

Sincerely,

the obsequious:

Respectfully,

and the even more craven:

V/r,

("Very respectfully"). The erudite Latinist may try:

Vale,

("Be healthy"). To a dear comrade one might venture:

Fondly,

in a relationship where the out-and-out:

Love,

is far too daring. But my personal favorite closing is simply the optimistic and ambiguous:

Best,

Sometimes an inadvertent typo renders this as:

Beset,

which is, alas, all too often accurate in these hectic times ...

- Monday, August 30, 2004 at 05:40:20 (EDT)

What ever happened to simple running, jumping, and throwing? Whither faster, higher, farther? Now, it's all about cash flow. I'm going out for a walk in the park --- at least that's real ...

(see also Something To Sell (14 Apr 2002), For Themselves (8 Jun 2003), Circus Sponsorus (10 Oct 2003), Professional Juicers (28 Jan 2004), ... )

- Sunday, August 29, 2004 at 13:30:34 (EDT)

What does that mean? Well, a few weeks ago while looking for information on the word "virii" (and whether it might be the proper plural of "virus") I chanced upon the following post to an online users group in January 2000:

Actually, the plural of the *Latin* word virus never occurs. This is partly for the same reason there is no plural of the English word "mud" - it's a collective - and partly because it's just one of those nouns that only occurs in a few forms - called a "defective". So it's a defective collective. The English word, which has a different meaning, might be called an infective defective collective. This letter is intended as an infective defective collective corrective. If you don't like it, send some infective defective collective corrective invective. But not to me, please. --- m.

A superb answer --- I promise never to write "virii" again. But who is this mystery man "m.", author of the above? Dr. "m." turns out to be Matt Neuburg [1], who besides being a Latin lover (like me!) writes free software (like me!) and was once a diehard Macintosh HyperCard enthusiast (like me!). Matt is also a fan of a free text information retrieval (like me!) and is a writer of articles about computer technology (like me!). In fact, some of Matt's essays cite my work. And on top of all that, Matt has implemented a computer version of Durak, a Russian card game that my daughter Gray [2] brought home from summer music camp and has taught to the family.

Sounds pretty far-fetched --- half a dozen or so 10-3 to 10-6 probabilities that multiply together to make an astronomically improbability. But of course it's not. The right question to ask is: "Of all the people in the world whom I might find via an Internet search for language trivia, how many have several other interests that match up with mine?"

From that perspective this isn't a 10-18 to 10-36 class coincidence at all. There are a large number of people with overlapping avocations (and vocations) in the world. Each person also has many different areas of expertise. So it's actually quite easy to find somebody with multiple factors in common --- particularly when those factors aren't specified in advance, but are recognized and highlighted after the fact. (That's the magical principle known as "The Conjuror's Choice".) Besides which, people who like word games often like card games; people who like words and computers often like free-text information retrieval; people who like user-interface toolkits often like free software; and so forth.

No, the real surprise here is that, until now, Matt and I haven't met one another ...

(one more coincidence: in correspondence, when I checked with him concerning the above, Matt told me that he was raised in Montgomery County --- where I've been living for the past few decades; see also Human Diffusion (19 Jan 2000), Voiced Postalveolar Fricative (27 Sep 2003), Rubensesque Passers By (24 Jul 2004), ... )

- Saturday, August 28, 2004 at 18:19:43 (EDT)

This year, in a wise move, the MCRRC has gathered more than a hundred of the most memorable articles from the Club newsletter/magazine (The Rundown) together and published them as a book. It's called What Do You Think of When You Run? and is simply delightful, a stew of advice, analysis, and anecdote that cuts across the widest spectrum of interest. I particularly enjoy the profiles of people whom I've met during my rambles along the trails. Sam Pizzigati [2] is a noteworthy author of these.

My only complaint: there's not enough poetry. Not any poetry, in fact. Maybe in another 25 years, at the next MCRRC quarter-century anniversary ...

(see also Jog Log Fog (9 Jun 2002), Jog Log Fog 4 (20 Apr 2003), Fading Traces (16 Apr 2004), Rock Creek Valley Trail (30 Apr 2004), Big And Strong (27 Jul 2004), Face Plant (9 Aug 2004), ... )

- Friday, August 27, 2004 at 06:28:07 (EDT)

| CAT IS MY COPILOT |

(see also Meta Joke (18 Oct 2001), Heavy Sleeper (19 Nov 2001), Meta Joke 2 (6 Dec 2001), Larger Inside (11 May 2004), ... )

- Thursday, August 26, 2004 at 05:48:43 (EDT)

To Donald Kent Stanford, Jr.

and to the other boys of all ages who admire fine cars

and good sportsmanship

I bought a copy of The Red Car a few months ago as a birthday gift for my son Robin (aka Rad Rob); more recently Paulette found a copy at the local library's used-book sale. Some excerpts that convey the spirit of Stanford's prose follow.

from Chapter Five, as the French mechanic explains some basic automotive design theory to the boys in front of a dismantled M.G. engine:

"Ah! It does not looks like much, hein? It is not very big, the little engine; it has but four of the so small pistons, like this one. How can such a little engine move a car as fast as, perhaps, eight very big cylinders will move the car of your friend, Lennie, eh? Well, I tell you, it will not --- not quite. Your friend has the power of more than one hundred horses; this little engine has the power of perhaps fifty-five, fifty-six. And so he can go, as I have heard him say, faster than can Steve Norton. It is true."

Frenchy waited, grinning, and Hap kept his mouth shut, and finally Shorty asked, puzzled, "Then --- then why ---? I mean, if an M.G. won't go as fast as a Ford, even, then what good is it? Isn't that what it's for, to go fast? To win races?"

"It is not to win races," Frenchy said, emphasizing the word, "but to win competitions of all sorts. In its class! You do not ask the little flyweight boxer to fight with the heavyweight champion, hein? This little engine has won all of the competitions in its class, it is the champion. Your friend Lennie, with an engine perhaps four times this size, develops only about twice its power, that is not very good. And with it he must move, we will say, nearly two tons of a soft fat automobile that will not go around a corner ver' well because it is too comfortable. Now, this little engine, it is not soft and it is not fat and it is not lazy; the four little pistons work very hard and very fast, and though they are only one-fourth the size of Lennie's they will produce half as much power. And with that power they do not have to move two tons of fat automobile, but less than one ton of very lean, hard automobile which is not very comfortable, but will go very fast around curves. . . ."

Frenchy then goes on to discuss cornering and engine displacement.

from Chapter Eight, as protagonist Hap Adams's father comes back to his senses after a too-fast first ride with his son in the red M.G.:

"However, I've got something serious to say, and I want to say it to all of you boys. I'd just started to say to Hap when you all came in --- that was a darn fool stunt! Now, I was just as much to blame as anyone --- I'd be obliged if you boys would refrain from telling it around --- but the fact is I got kind of carried away myself. I was urging Hap on to race you, Lennie. A man can be just as foolish as a boy; he just doesn't get caught at it so often.

"But driving at that speed, on the open road --- that's for fools! Granted the highway was clear, granted neither of us took any foolish chances in passing, granted both of you boys kept your cars under control --- it's still dangerous, and stupid! Suppose somebody else did come around one of those curves, and you saw him in plenty of time but just then you blew a tire? It isn't fair to other people to make them share your risk! I hope I never hear of any of you doing anything like it again; if Hap ever does, he loses his car, and that's final. Understand?"

Mr. Adams continues, however, to muse in favor of safe, well-managed auto racing.

... and shortly thereafter, much to the consternation of his son Mr. Adams leads Hap to a fashion shop down the street where he selects a sophisticated cocktail dress for his wife:

"We'll have that black one with no top to speak of, I think," he said, taking the pipe out of his mouth long enough to speak with clear decision, and then stuck it back in and mumbled something that sounded like, "Your mother has scandalously pretty shoulders. Come on, son."

Struck dumb with surprise, Hap followed silently into the shop, and stood by speechless while his father bought the dress and had it wrapped and paid for it, and finally stuffed his change into his wallet and tucked the box under his arm.

As they prepare to go home Hap attempts to figure out the logic behind his father's purchase. Finally Mr. Adams explains:

He pointed the stem of his pipe at Hap, and said, "Remember this, son: a luxury is a thing that's perfectly unnecessary, perfectly useless. It's a thing people don't need, but want; and the more useless it is the more they want it, just to have it and love it. And everybody ought to have one luxury, one useless thing he loves just to have. Even people who can't afford luxuries, like us; maybe especially people like us . . "

He paused, and his eyes twinkled briefly, and he said dryly, "That is truth, that bit of philosophy. It is also what we are going to try to sell your mother, when we come home with this absolutely unnecessary, wildly impractical, perfectly useless car of yours. We'll give her her present first; if she likes it as well as I think she will, knowing your mother as I sometimes dare to think I do, you're in. We have only to point out, then, when she sees the car, that she has something useless to love, and certainly you should have the right to the same luxury. Right?"

They had reached the M.G., and Mr. Adams stood by while Hap unbuttoned the canvas boot that covered the folded-down top and revealed a luggage well big enough to stow the dress box in. It took him more than a minute to put the box away, and he did not speak at all during that time; he was lost in thought. What his father had said seemed to him to be very true and very profound. He knew he would not forget it for a long time; he hoped he would never forget it. He understood now why his father had bought this extravagant and impractical dress instead of, say, the steam iron his mother had mentioned wanting; he understood --- and knew that his father understood and approved, now --- another part of the reason he loved the M.G. so. ...

(see also Detectives In Togas (6 Aug 2003), Bronc Burnett (1 Jul 2004), ... )

- Wednesday, August 25, 2004 at 06:12:02 (EDT)

"Wow, Nothing! Just what I always wanted!"

... over an empty box.

(see also So Funny (10 Aug 1999), No Concepts At All (22 Feb 2001), Zen Scrabble (7 Jan 2002), More Fun Less Stuff (1 Oct 2002), ... )

- Tuesday, August 24, 2004 at 06:23:42 (EDT)

My favorite jargonism of all time, however, is the mysterious "O.B.E.", as in "You don't have to do that; it's O.B.E. now."

When I first heard it I thought "O.B.E." might mean "Order of the British Empire", a famous award for honorable service to the United Kingdom. (How sweet --- some helpful Englishman with a medal is going to do my work for me!) But alas, "O.B.E." simply means "Overtaken By Events". That is, it's too late now to be worth bothering with any more. Given bureaucratic delays, this is a common term ...

- Monday, August 23, 2004 at 06:17:44 (EDT)