^zhurnaly 0.9951

Howdy, pilgrim! You're in the ^zhurnal — since 1999, a journal of musings on mind, method, metaphor, and matters miscellaneous — previous volume = 0.9950. For the whole ZhurnalyWiki in experimental TiddlyWiki form, load https://zhurnaly.tiddlyhost.com/ (~20MB, may take a few seconds) – a backup snapshot is at http://zhurnaly.com/zhurnalywiki.html. For a static snapshot of the ZhurnalyWiki's 8,900+ individual pages, see http://zhurnaly.com/z/. For experimental insight-generation suggestions see https://insight.tiddlyhost.com ... Send comments and suggestions to z "at-sign" his.com — thank you!

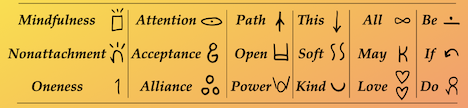

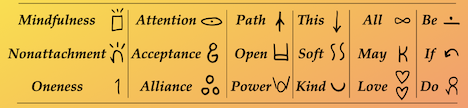

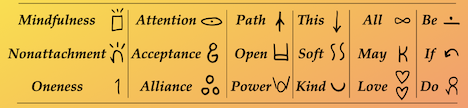

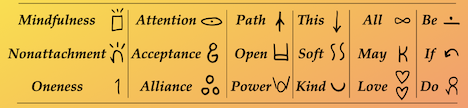

And see Insight Dice for a new experiment in Mindfulness + Nonattachment + Oneness!

Being You

Anil Seth, professor of cognitive and computational neuroscience, in his 2021 book Being You: A New Science of Consciousness does an excellent job of examining big, important ideas about mind and mathematics, intelligence and evolution. What Seth calls "the real problem of consciousness" is to "explain, predict, and control the phenomenological properties of conscious experience" — that is, understand the connections between patterns of body-brain activity and subjective experiences. This is better-defined than the fuzzy-philosophical so-called "hard problem" of the relationship(s) between mind and body.

Seth argues that progress is possible on the real problem in much the same way that progress was made on understanding life during the past century. Biologists and chemists worked on "describing the properties of living systems, and then explaining (also predicting and controlling) each of these properties in terms of physical and chemical mechanisms." Seth concludes that what seems impenetrably mysterious about mental phenomena now may not always be incomprehensible — once the underlying mechanisms are figured out for components of consciousness.

There's much more to be said, and the bulk of Being You is devoted to examining various facets of consciousness. The three big themes are:

- level — the amount of consciousness we have, from nothingness up to full awareness

- content — what we are conscious of, including sensations, emotions, thoughts, beliefs

- self — the experience of "being you", inhabiting a particular body, having memories of the past, feeling a "free will" ability to make choices, etc

Seth discusses objective measures of brain neural activity and their connections to mental states via the "Integrated Information Theory" of consciousness — "IIT". He explains the "top-down" theory of perception, specifically "controlled hallucination" and how:

- "the brain is constantly making predictions about the causes of its sensory signals, predictions which cascade in a top-down direction through the brain's perceptual hierarchies"

- "sensory signals — which stream into the brain from the bottom up, or outside in — keep these perceptual predictions tied in useful ways to their causes ... as prediction errors registering the differences between what the brain expects and what it gets ... [so] perception happens through a continual process of prediction error minimization"

- perceptual experience "is determined by the content of the (top-down) predictions, and not by the (bottom-up) sensory signals. We never experience sensory signals themselves, we only ever experience interpretations of them."

In other words, stand the usual notion on its head: conscious minds don't see the world through sensory organs, but rather they see a "hallucination", internally generated and updated based on prediction errors.

That's an awesome inversion, one that needs much work to wrap one's mind around. Seth provides excellent examples, explains Bayesian reasoning, and offers good evidence to make a strong case for that new model of mind. He discusses other kinds of consciousness, in animals and machines. He examines the challenges of controlling bodies in the countless ways needed to stay alive, thrive, and reproduce. He distinguishes between intelligence and consciousness, and explores moral issues as well as technological ones.

| Bottom line: Being You is a wonderful tour of an important emerging field of science, worth reading and re-reading. |

(cf The Mysterians (1999-08-02), Thoughtful Metaphors (2000-11-08), Conscious Mind (2013-06-22), ...) - ^z - 2023-11-01

- Wednesday, November 01, 2023 at 21:47:17 (EDT)

Is Math Real?

Eugenia Cheng's new (2023) book "Is Math Real? How simple questions lead us to mathematics' deepest truths" is a chatty general-audiences discussion of what mathematicians do, and why. In the Introduction Dr Cheng summarizes the entire enterprise:

| "... Deep down, math isn’t about clear answers, but about increasingly nuanced worlds in which we can explore different things being true. ..." |

The book is rich in geometric examples, personal asides, fascinating trivia, and more. Again from the Intro:

For me, math is also about making something myself: it’s about making truth myself. It’s about being self-sufficient out in the wild world of ideas. This, to me, is an immensely exciting, daunting, awe-inspiring, and ultimately joyful experience, and this is what I want to describe. I want to describe what math feels like, in a way that is quite different from how it’s often thought of. I will describe the expansive side of math, the creative, the imaginative, the exploratory, the part where we dream, follow our nose, listen to our gut instinct, and feel the joy of understanding, like sweeping away fog and seeing sunshine. This is not a math textbook, nor is it a math history book. It’s a math emotions book.

... and from Chapter 4 ("What Makes Math Good"), a lovely description of qualities that mathematicians share:

I’m not sure what it takes to be a great anything, but to be a good mathematician you don’t have to be any of those particular things. You need to be open-minded and be able to think flexibly, and be able to see things from many different points of view at the same time. You need to be able to see connections, which often means being able to ignore certain details about a situation in order to see how it matches up with another when those certain details are ignored. But you also need to be flexible enough to put those details back in, and ignore different ones to see things differently. You need to be able to construct highly rigorous arguments, hold them in your brain, move them around, and fit them together with other highly rigorous arguments. And you need a tolerance, or even a thirst, for the increase in manufactured complexity that this brings with it. This also involves creating ways to deal with that complexity, like creating special eggs and then creating a special egg carton to carry them around in. And then creating a special crate for the special egg cartons, and then perhaps a special truck for those special crates, and so on. Thus it often involves building up gradually bigger and bigger dreams from smaller ones, so it calls for a vivid imagination and ability to bring weird and wonderful ideas to life in your head. There is a myth that math and science are separate from “creative” subjects in the arts, but the line between them is really quite blurry. The myth probably comes from thinking that math is just about step-by-step computations with clear answers. But note that in describing a good mathematician, I did not at any point mention arithmetic, computation, memorization, numbers, or getting the right answers. Some computational parts of math do involve computation, but not all math is computational.

Is Math Real? isn't a "deep" book in a technical-mathematical way; it's deep in philosophy, thoughtfulness, and kindness. Good!

(cf Cakes, Custard, and Category Theory (2016-02-14), Ingressive vs Congressive (2017-07-08), Beyond Infinity (2017-07-24), Ultimate Abstraction (2017-08-24), Eugenia Cheng on Thinking (2017-12-30), Many Worlds of Math (2019-03-15), Eugenia Cheng on Category Theory (2023-03-26), ...) - ^z - 2023-11-01

- Wednesday, November 01, 2023 at 09:02:35 (EDT)

Relaxation and Stress Reduction

The Relaxation and Stress Reduction Workbook by by Martha Davis, Elizabeth Robbins Eshelman, and Matthew McKay was recommended recently in Hope Reese's "Feeling Stressed? These 5 Books Can Help". It's rather pedestrian in style, and prone in places to false precision or overly-certain quick-fix prescriptions. But there are insights, like the list in Chapter 5, "Meditation":

- It is impossible to worry, fear, or hate when your mind is thinking about something other than the object of these emotions.

- It isn’t necessary to think about everything that pops into your head. You have the ability to choose which thoughts you will think about.

- The seemingly diverse contents of your mind really can fit into a few simple categories: grudging thoughts, fearful thoughts, angry thoughts, wanting thoughts, planning thoughts, memories, and so on.

- You act in certain ways because you have certain thoughts that over your lifetime have become habitual. Habitual patterns of thought and perception will begin to lose their influence over your life once you become aware of them.

- Emotions, aside from the thoughts and pictures in your mind, consist entirely of physical sensations in your body.

- Even the strongest emotion will become manageable if you concentrate on the sensations in your body and not the content of the thought that produced the emotion.

- Thoughts and emotions are not permanent. They pass into and out of your body and mind. They need not leave a trace.

- When you are awake to what is happening right now and open to what is, the extreme highs and extreme lows of your emotional response to life will disappear. You will live life with equanimity.

All good! — though expressed rather too strongly and without qualifiers. Other parts of the "Meditation" are beautifully written, especially some of the suggestions for how to focus, relax, let go, and accept. They're reminiscent of another book of the five recommended in Hope Reese's article: Wherever You Go, There You Are by Jon Kabat-Zinn.

(cf Softening into Experience (2012-11-12), Equanimity and Magnanimity (2015-02-19), This Is Equanimity (2015-03-15), Stress Storm (2019-12-26), Worry, Stress, Anxiety (2020-03-04), Resilience Training (2022-10-03), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-30

- Monday, October 30, 2023 at 08:34:04 (EDT)

Nature and Nurture

Genetics Loads The Gun

Environment Pulls the Trigger |

... on the heritability of traits, and their expression!

(cf Three Equations for Life (2020-05-03), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-30

- Monday, October 30, 2023 at 07:06:40 (EDT)

Brief History of the Female Body

Deena Emera's delightful (2023) book A Brief History of the Female Body: an evolutionary look at how and why the female form came to be delivers precisely what its title promises. It's a scientific overview of how evolution by natural selection drove the emergence of human physical designs, reproductive systems, and developmental strategies. And in additional to sharp technical commentary, Dr Emera is funny and engaging in discussing her personal experiences as a mother and evolutionary biologist. She reviews how life in other species on Earth met analogous challenges over the eons. She is meticulous in describing current research, open questions, alternative hypotheses, and gaps in the data. Key topics include everything from chromosomes to breasts, menstrual periods to orgasms, pregnancy to menopause, and children to grandmothers. All are treated with a light touch as well as, when needed, deep detail (though no equations). Worthwhile reading on many levels!

(cf Light of Evolution (2006-04-24), Darwin on Altruism (2006-10-31), Darwin in Conclusion (2007-01-05) ...) - ^z - 2023-10-29

- Sunday, October 29, 2023 at 08:03:28 (EDT)

Mantra - Words in the Language of God

All Beings are Words

In the Language of God |

... a metaphor by William Irwin Thompson, as quoted by Sallie Tisdale — possibly in the book The Time Falling Bodies Take to Light ...

(cf Talk Dirty to Me (2014-04-08), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-27

- Friday, October 27, 2023 at 13:31:10 (EDT)

Be You, Only Better

Be You, Only Better by Kristi Hugstad, is a short, cheerful guide to "real-life self-care for young adults (and everyone else)", as per its subtitle. The chapters and their sub-heads say it all quite nicely:

- Write It Down (daily journaling)

- Get Good Sleep

- Get Up and Move (exercise)

- Embrace Nature (go outside)

- Cut Down on Sugar (eat healthy)

- Manage Your Time

- Manage Your Money

- Have Healthy Relationships (with your self, friends, family, and romantic partners)

- Be Mindful (self-awareness)

- Be Grateful (positive mental attitude)

- Hope (optimism)

... all excellent suggestions!

(cf Optimist Creed (1999-04-16), Bennett on Life (2000-03-19), Just One Thing (2012-12-02), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-27

- Friday, October 27, 2023 at 10:31:36 (EDT)

Mantra - Sit with the Void

Sit with the Void

instead of

Trying to Fill It |

... about the need for deep patience and self-knowledge when seeking love in one's life — from an NY Times essay by Annie Dwyer, which ends with:

Recently, my children and I were talking and laughing together, and it was the brightest joy. I remembered how the man with the red thread said I didn’t lose. He was right. I also remembered how he struggled with fantasy. “I need to learn how to sit with the void instead of trying to fill it,” he had explained.

At the time, I didn’t understand what he meant, but now I do. I’ve had to learn how to sit with the void too. I’ve needed to be present and love myself.

I’m no longer embarrassed that my path is unusual. I look in the mirror and feel such tenderness for the woman I see. I smile, thinking: It’s already been a full life. And there’s still time.

(cf No Thing and Every Thing (2015-09-20), Mantra - Gap (2015-11-11), Mantra - No Self (2016-10-25), Nobody Home (2016-11-13), Mantra - Be the Silence (2016-12-10), Not All About Me (2018-02-18), Mantra - Be Meta, Be Open, Be Love (2018-11-11), Compassion and Balance (2023-05-17), Bubble of Peace (2023-07-05), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-27

- Friday, October 27, 2023 at 08:18:45 (EDT)

Friday Barnes, Big Trouble

Big Trouble: A Friday Barnes Mystery, third in the series of R. A. Spratt novels, follows the path of its predecessors in pre-teen detective work, with snappy dialogue between the hyper-quantitative title character and her idiosyncratic-orthogonal roommate-best-friend Melanie. The girls each view the world from their unique perspectives. Result: delightful humor!

An example, from Chapter 12 ("A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words"), as Friday and Melanie examine a gossip magazine photo of two of their fellow boarding-school students apparently embracing, captioned "Secret Smooching at Swanky School":

"The first thing we've got to figure out," said Friday,

"is where the photo was taken."

"At the school," said Melanie.

"Yes, obviously," said Friday. "But where at the school? It's hard to work out because the photo is black-and-white and the background is fuzzy."

"Plus you're in love with lan," said Melanie. "So you can't take your eyes off his lips."

"I am not in love with Ian," said Friday.

"Uh-huh," said Melanie. "And yet here you are, staring at a photo of him."

"I'm looking at the background!" said Friday.

"Of course you are," said Melanie. "Maybe you should look at his hair."

"I'm not obsessed with his hair," said Friday.

"No, I mean the angle of it," said Melanie. "It's strange."

"Maybe Ingrid ran her hand through his hair," said Friday. "That is something kissing people are known to do."

"How would you know? asked Melanie.

"We didn't only have physics books in our house growing up," said Friday. "There was a small sociology section, too."

"Still," said Melanie, "his hair seems to be defying gravity."

Friday looked at lan's hair. "You're right."

"I am?" said Melanie. "That's a nice change."

Friday tilted her head. "This photograph is at the wrong angle." She turned the magazine around. "They aren't standing up. They're horizontal."

"Ew," said Melanie, shielding her eyes. "Too much information.

"We need to talk to the victims," said Friday.

"My eyeballs?" asked Melanie.

...

Fast, fun, a bit more picaresque than the prior books in the series — and all good!

(cf Friday Barnes, Girl Detective (2023-10-18), Friday Barnes, Under Suspicion (2023-10-23), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-26

- Thursday, October 26, 2023 at 07:22:52 (EDT)

Friday Barnes, Under Suspicion

Book 2 in the "Friday Barnes, Girl Detective" series by R. A. Spratt, Under Suspicion, continues the tween-fiction-mystery in entertaining directions – including sly asides involving physics ("M-Theory" and "electroweak bosons"), physiology ("benign positional paroxysmal vertigo"), classic myth ("Sisyphean"), and other break-the-vocabulary-list terms. There's snappy dialog, pre-teen pre-romance humor, and cute sleuth action. Fast and fun, like its predecessor!

^z - 2023-10-23

- Monday, October 23, 2023 at 09:51:16 (EDT)

David Brooks on Being Human

"The Essential Skills for Being Human" by David Brooks is a thoughtful essay adapted from his new book How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen. Brooks discusses how to connect — crucial skills for helping self, others, and World:

... Being openhearted is a prerequisite for being a full, kind and wise human being. But it is not enough. People need social skills. The real process of, say, building a friendship or creating a community involves performing a series of small, concrete actions well: being curious about other people; disagreeing without poisoning relationships; revealing vulnerability at an appropriate pace; being a good listener; knowing how to ask for and offer forgiveness; knowing how to host a gathering where everyone feels embraced; knowing how to see things from another’s point of view.

Brooks defines diminishers and illuminators:

... In any collection of humans, there are diminishers and there are illuminators. Diminishers are so into themselves, they make others feel insignificant. They stereotype and label. If they learn one thing about you, they proceed to make a series of assumptions about who you must be.

Illuminators, on the other hand, have a persistent curiosity about other people. They have been trained or have trained themselves in the craft of understanding others. They know how to ask the right questions at the right times — so that they can see things, at least a bit, from another’s point of view. They shine the brightness of their care on people and make them feel bigger, respected, lit up.

Brooks lists the "skills illuminators possess":

- The gift of attention — "a gaze that communicates respect"

- Accompaniment — "an other-centered way of being with people during the normal routines of life" — "the art of presence, just being there"

- The art of conversation

- Be a loud listener — provide "encouraging affirmations"

- Storify whenever possible — help others talk "about the people and experiences that shaped their values"

- Do the looping — paraphrase back, to correct misimpressions

- Turn your partner into a narrator — "ask specific follow-up questions" to elicit richer stories

- Don’t be a topper — avoid responding with your own experiences and shifting attention back to yourself

- Ask "Big questions" — "ones that lift people out of their daily vantage points and help them see themselves from above", such as:

- What crossroads are you at?

- If the next five years is a chapter in your life, what is the chapter about?

- Can you be yourself where you are and still fit in?

- What would you do if you weren’t afraid?

- If you died today, what would you regret not doing?

- What have you said yes to that you no longer really believe in?

- What is the gift you currently hold in exile? — meaning, what talent are you not using?

- Why you? — meaning, what is your motivation for what you did?

- Stand in their standpoint — "ask other people three separate times and in three different ways about what they have just said" — "show persistent curiosity" about other people's viewpoints

Brooks describes those who are most helpful:

The really good confidants — the people we go to when we are troubled — are more like coaches than philosopher kings. They take in your story, accept it, but prod you to clarify what it is you really want, or to name the baggage you left out of your clean tale. They’re not here to fix you; they are here simply to help you edit your story so that it’s more honest and accurate. They’re here to call you by name, as beloved. They see who you are becoming before you do and provide you with a reputation you can then go live into.

Echoes of Cardinal Newman's "Definition of a Gentleman", eh?!

(NYT-gift-link - cf Cardinal Newman (2001-10-04), Discussion and Dialogue (2006-01-07), AntiArrogance (2007-12-24), True Gentleman (2008-07-10), Eagles Are All about Efficiency (2020-05-12), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-21

- Saturday, October 21, 2023 at 12:58:09 (EDT)

All the World's Babies

A powerful, wise, loving, peaceful metaphor:

A nation is defined as a group of people with a common language, a common past and common dreams. By this definition, any parent will tell you that all the world’s babies are children of a single nation. They have a common language, a common past, common dreams. They speak the same, get angry and cry at the same things, laugh the same way. When my three children were young, I marveled at how they communicated effortlessly with other babies, no matter the language of the lullabies their parents sang them at night.

... from "All the World’s Babies Are Children of a Single Nation" by Ayman Odeh, in a New York Times essay calling for peace:

The whole of this nation of infants — Jewish, Arab, Palestinian, Israeli — wants just one thing: to grow up to a good life. It’s a simple dream. Our role as leaders is simple too: to make that possible.

As adults, we all become expatriates of that nation, and we take the dream of a good life with us: To put food on the table for our families. To know we are free to go where we want. To speak, pray and celebrate as we like. To come home safely at the end of the day. To know our loved ones will too.

NYT gift-link - (cf Our Balance Sheet (1999-09-22), Independence Day (2001-07-04), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-19

- Thursday, October 19, 2023 at 08:04:19 (EDT)

Friday Barnes, Girl Detective

What a great paragraph — in a novel that says it's for "ages 8-12" — as protagonist Friday Barnes confers with her best friend Melanie:

Friday sighed. There was no point arguing with Melanie. Words had very little semiotic meaning for her. She usually lost concentration somewhere between the beginning and the end of a sentence.

... and later on that same page:

... Friday had received an A+ for her presentation on Rosalind Franklin and how Watson, Crick, and ovarian cancer had combined to cheat her out of a Nobel Prize for her role in the discovery of the structure of DNA. ...

That's not atypical prose for R. A. Spratt's book Friday Barnes, Girl Detective. It's a delightful fast-paced tongue-firmly-in-cheek first-in-a-series of stories featuring a scary-smart somewhat-shy socially-skewed young lady who solves crimes and other mysteries. The author is Australian, and (judging by an interview with her) much like her central character. Highly recommended for all who cherish cleverness and silly fun.

(cf Three Man Boat (2002-01-10), Detectives in Togas (2003-08-06), Frog and Toad (2009-01-09), Enchanted Castle (2010-07-17), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-18

- Wednesday, October 18, 2023 at 21:39:51 (EDT)

Princess Diaries

Recommendation from a good friend: The Princess Diaries, a young adult novel by Meg Cabot. Best bit: the quote at the beginning from Frances Hodgson Burnett's A Little Princess:

| "Whatever comes," she said, " cannot alter one thing. If I am a princess in rags and tatters, I can be a princess inside. It would be easy to be a princess if I were dressed in cloth of gold, but it is a great deal more of a triumph to be one all the time when no one knows it." |

Princess Diaries is cute and silly. Deep? Not very. Naughty? Only a wee bit. Framework? A series of journal entries by a young lady, over a three-week period, as she learns that she's the crown heir of a tiny European nation. Discovery? Her prior teen troubles are radically changed into new, albeit equally tiny, troubles. Bottom Line? Hmmmmmm ... hard to say. First in a series of a dozen books plus some films. Fast and fun reading.

^z - 2023-10-15

- Sunday, October 15, 2023 at 11:18:13 (EDT)

Other Minds

Peter Godfrey-Smith's 2016 book Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness is a fun, fast romp through evolutionary biology, philosophy of mind, neurophysiology, and the author's personal relationships with cephalopods as a scuba diver. It raises an ocean of questions and suggests some potential answers. As Godfrey-Smith says in the first chapter, "Doing philosophy is largely a matter of trying to put things together, trying to get the pieces of very large puzzles to make some sense." Some big takeaways from Other Minds include:

- maybe we can better understand neural activity by looking at how it arose in distinct branches of the tree of life that forked hundreds of millions of years ago – among vertebrates (mammals, birds, fish, ...) and more distantly among mollusks (especially octopuses, cuttlefish, and squid)

- nervous systems have two main functional purposes:

- sensory-motor — to link data perceived from the environment with muscular responses

- action-shaping — to coordinate and enable complex or large-scale motions based on local micro-acts of body parts

- "inner speech" and spatial imagery seem to be important parts of human cognition, but "very complex things go on inside other animals without the aid of speech"

- consciousness and more general subjective experiences may arise along a continuum, not abruptly — "There's a smooth transition from minimal kinds of sensitivity to the world to more elaborate kinds, and no reason to think in terms of sharp divides" — beginning perhaps with "primordial emotions" such as pain, thirst, suffocation, hunger, sexual arousal, etc.

- lifespans of creatures are driven by evolution and the cost-benefit tradeoffs of mutations on different timescales

Godfrey-Smith summarizes near the end of Chapter 7:

The lifespans of different animals are set by their risks of death from external causes, by how quickly they can reach reproductive age, and other features of their lifestyle and environment. That is why we can live for about a century, a nondescript fish can live for twice as long, a pine tree's life can run from John the Baptist's to your own, and a giant cuttlefish—with its wild colors and friendly curiosity—arrives and is gone in a couple of summers.

In the light of all this, I think it is becoming clearer how cephalopods came to have their peculiar combination of features. Early cephalopods had protective external shells which they dragged along as they prowled the oceans. Then the shells were abandoned. This had several interlocking effects. First, it gave cephalopod bodies their outlandish, unbounded possibilities. The extreme case is the octopus, with almost no hard parts at all, and neurons spread through the body instead of bones. Back in chapter 3 I suggested that this open-endedness, this sea of behavioral possibility, was crucial to the evolution of their complex nervous systems. It's not that the loss of a shell alone created the evolutionary pressure leading to those nervous systems. Rather, a feedback system was established. The possibilities inherent in this body create an opportunity for the evolution of finer behavioral control. And once you have a larger nervous system, this makes it worthwhile to further expand the body's possibilities—collecting all those sensors on the arms, creating the machinery of color change and a skin that can see.

The loss of the shell also had another effect: it made the animals much more vulnerable to predators, especially fast-moving fish, with bones and teeth and good vision. That put a premium on the evolution of wiles and camouflage.

But there is only so much those tricks will achieve, only so many times they will save the animal. An octopus can't expect to live a long time, especially as they must be active as predators themselves. They can't just hide in a hole and wait for food to come to them. They have to be out and about, and once in the open they are vulnerable. This vulnerability makes them ideal candidates for the Medawar and Williams effects to compress their natural lifespan; a cephalopod's lifespan has been tuned by the continual risk of not making it to the next day. As a result, they have ended up with their unusual combination: a very large nervous system and a very short life. They have the large nervous system because of what those unbounded bodies make possible and the need to hunt while being hunted; their lives are short because their vulnerability tunes their lifespan. The initially paradoxical combination makes sense.

And besides conceptual insights, Other Minds also has lots of stories and photographs of cute octopuses!

(cf Bits of Consciousness (2000-01-21), Suffer the Animals (2000-06-11), Drawing the Line (2004-07-11), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-12

- Thursday, October 12, 2023 at 15:02:43 (EDT)

Placebo Effect

"No Better Than a Placebo" by Ted Kaptchuk (NYT 2023-10-10) explains some of the complex psycho-physical issues surrounding health:

To date, the best explanation for the results of open-placebo trials suggests that for certain illnesses in which the brain amplifies symptoms, engaging in a healing drama can nudge the brain to diminish the volume or false alarm of what’s called central sensitization — when the nervous system overemphasizes or amplifies perceptions of discomfort. This mostly involves nonconscious brain processes that scientists call Bayesian brain, which describes how the brain modulates symptoms. The intensification and the relief of symptoms use the same neural pathways. Considerable evidence also shows that placebos, even when patients know they are taking them, trigger the release of neurotransmitters like endorphins and cannabinoids and engage specific regions of the brain to offer relief. Basically, the body has an internal pharmacy that relieves symptoms.

So placebos should be used – with full recognition of both their benefits and limitations: "[They] shouldn’t be a first-line treatment; patients should be given what effective medicines are available. After all, placebos rarely, if ever, change the underlying pathology or objectively measured signs of disease. I like to remind people that they don’t shrink tumors or cure infections."

Kaptchuk's bottom-line conclusion is a crucial one:

| ... rituals, symbols and human kindness matter immensely when it comes to healing. |

(cf Medicine and Statistics (2010-11-13), Dizzy Doc (2023-06-22), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-11

- Wednesday, October 11, 2023 at 08:28:28 (EDT)

Paul Bloom on How to Teach

In "Diminishing returns and tripping balls" psychology professor Paul Bloom offers excellent advice on how to be a great teacher. Abridged and arranged to include Bloom's additional commentary:

- Enthusiasm. When you’re in class, you should act like there’s no place in the world you’d rather be. Enthusiasm is infectious ...

- Confidence. ...

- Mix it up. Don’t just do the same thing over and over again, throw in some variety. ...

- Bring in other people. ... [but this] is risky, particularly for a lecture class. Most guest lecturers are awful (most lecturers are awful) ...

- Be modest in your goals for each class. The most common mistake of beginning teachers is cramming too much material in any single session. ...

- Be yourself. Everyone has strength; teach in a way that aligns with what you’re good at. ...

- Teaching prep can leech away all your time; don’t let it. Say to yourself: Diminishing Returns. Then say: Opportunity Costs. Repeat as needed.

- A well-timed “Great question. I don’t know — but I’ll find out for next class” is really charming and makes everyone feel good. ...

- Use specific students as examples in arbitrary ways. ...

- . ... Every question a student asks is, at minimum, “Interesting!”. If it’s total gibberish, go for something like: “Parts of your question might go a bit too far beyond our topic for today, but one of your points raises something really neat ...” ...

- Use concrete examples whenever possible ...

- Many good teachers self-medicate before class, especially if they suffer from anxiety. ...

- At least for the first class, get there early, and make small talk with the students who are also there early. ...

- Take notes after class about what worked and what didn’t. ...

- You have a captive audience that relies on you for your grades. ... Don’t abuse this. ... Be [expletive] professional.

- If you can help it, don’t swear unnecessarily.

- [Avoid] having students give presentations in seminars. Most student presentations are awful (of course they are—it’s really hard to give a good presentation; as I said above, most professors give awful presentations) and while the students might get something out of preparing and presenting, it’s boring for everyone who has to listen.

- ... make sure that every student talks in every meeting of a seminar. ...

- Remember: It’s not about you.

(cf Tufte Thoughts (2000-12-18), Helpful Homilies (2007-09-02), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-09

- Monday, October 09, 2023 at 15:21:52 (EDT)

Mantra - Less I, Less Me

Send the self off-stage sometimes, and give the starring rôles to others — start sentences with fewer first-person pronouns — turn the knobs on the Utility Function to place greater weight on the rest of the universe — open more windows, doors, eyes, ears, arms, mind ...

... so magically, everything becomes easier, quieter, more graceful, less brittle, and perhaps infinitely happier!

(cf Unselfing (2009-01-14), Unselfing Again (2009-11-01), Mantra - Let Others Be (2015-11-19), I Want Happiness (2015-12-04), Mantra - Cling to Nothing (2016-04-17), Mantra - Unself Together (2018-03-30), Less I (2018-05-26), Less Me (2021-12-14), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-06

- Friday, October 06, 2023 at 07:43:16 (EDT)

Nasty, Brutish, and Short

"Ask Questions, and Question Answers!" Think of Socrates as a comedian, with little children as his props. That's what Scott Hershovitz's book Nasty, Brutish, and Short: Adventures in Philosophy with My Kids is about: deep issues, explored entertainingly as dialogues with his two sons, plus extensive asides and commentary. Major themes, as per chapter titles:

- Rights

- Revenge

- Punishment

- Authority

- Language

- Sex, Gender, and Sports

- Race and Responsibility

- Knowledge

- Truth

- Mind

- Infinity

- God

Among the best bits, from the Introduction ("The Art of Thinking"), on how to read the book:

... That's one of the things I love about philosophy: you can do it anytime, anywhere, in conversation with others or all by yourself. You just have to think things through.

To that end, I want you to read this book a bit differently than you would many others. Most nonfiction writers want you to believe the things they say in their books. They're hoping that you'll accept their authority and adopt their way of thinking about the world.

That's not my aim at all. Sure, I'd like to persuade you to see things my way. But the truth is: I'm happy for you to think differently—as long as you've thought it through. In fact, I suggest that you approach the arguments I offer skeptically. Don't assume that I'm right. In fact, assume that I've gone wrong somewhere, and see if you can spot the spot.

But do me a favor. Don't just disagree. If you think I'm wrong, work out the reasons why. And once you've done that, think through what I might say in response. And how you'd reply, and what I'd retort. And so on, until you feel like you aren't learning anything anymore. But don't give up too quick; the further you go, the more you understand.

That's how philosophers work (at least the grown-up ones). I tell my students: when you have an objection to another philosopher's work, you should assume that she already thought of it—and that she thought it so misguided it wasn't even worth mentioning. Then you should try to work out why. If you give it a good try and you can't figure out where you've gone wrong, it's time to tell other people about it. The goal is to get in the habit of treating your own ideas as critically as you treat other people's. ...

... and in the chapter "Mind", on the importance of not coming to conclusions prematurely:

... Jules Coleman has been a friend and mentor for decades. He was my teacher in law school. And he taught me one of the most important lessons I ever learned.

I saw him in the hall when I was a student, and we started to talk philosophy. I can't remember what the question was. But I do remember attempting to share my view.

"In my view . . ." I started.

He cut me off.

"You're too young to have views," he said. "You can have questions, curiosities, ideas . . . even inclinations. But not views. You're not ready for views."

He was making two points. First, it's dangerous to have views, because often you dig in to defend them. And that makes it hard to hear what other people have to say. One of Coleman's signal virtues as a philosopher is his willingness to change his views. That's because he's more committed to questions than answers. He wants to understand,and he's willing to go wherever his understanding takes him, even if it requires him to backtrack from where he's been before.

Second, you have to earn your views. You shouldn't have a view unless you can defend it, make an argument for it, and explain where the arguments against it go wrong. When Coleman said I was too young for views, he wasn't really making a point about age. (I was twenty-six.) He was saying I was too new to philosophy. Decades on, I have lots of views. I can say why I hold them and where I think others go wrong. But I don't have views on every question, because I haven't done the work to earn them. ...

Bottom line: Nasty, Brutish, and Short is full of fine stuff, though at times perhaps it gets a bit too personal-narrow, with too much foul language and too much bias toward what-would-be-nice-if-it-were-true currently-conventional political beliefs. But that's ok – the reader has already been warned not to accept "answers" unquestioningly! Worth reading, and pondering.

(cf Living Philosophy (1999-06-12), Deliberate Opinion (2001-10-14), Robert Nozick (2002-02-02), Most Important (2002-05-16), Think Again (2002-08-29), No Dogs or Philosophers Allowed (2003-10-13), Discussion and Dialogue (2006-01-07), Question Answers (2016-10-09), Philosophy Now (2019-08-18), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-02

- Monday, October 02, 2023 at 17:10:10 (EDT)

Jimmy Buffett, R.I.P.

Lovely thoughts and quotes from Maureen Dowd's NYT column "Living and Dying in ¾ Time", celebrating the life of Jimmy Buffett (1946-2023):

“Well, I have learned one thing from my latest in a series of the ever-appearing speed bumps of life — 75 is NOT the new 50,” he emailed me. “Thinking younger doesn’t quite do it. You still have to do the hard work of, as the Toby Keith song says, ‘Don’t let the old man in.’ And that is my job now, the way I see it.”

and

“I have always loved books, reading and libraries, a gift from my mother,” Jimmy said. “The Library of Congress is a monumental treasure you don’t have to dig up; you just walk in the door of American history. ‘Margaritaville’ in the Library of Congress. I just have to giggle, but with pride. I haven’t received many awards in my profession, but I am OK with that. I think the best reward for a performer is to please the audience.”

and

But in the last couple of years, he often wrote from less exotic places, Boston and Houston, where he was being treated for an aggressive form of skin cancer, Merkel cell carcinoma. (Was there a price for trademarking the sun? Even so, I bet he wouldn’t have changed a thing.) He stayed upbeat on the “juice,” as he called his infusions to treat the cancer, and spoke proudly about his “all-female doctor team dedicated to keeping the old man out” on the road. He would say he had to “go into the pits for some adjustments” and reassure me that he was getting “weller.” He called it an irritation, a Southern fingernail on an English chalkboard.

(cf Bennett on Life (2000-03-19), Charles Lambiana (2000-10-24), Old Age (2007-05-22), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-02

- Monday, October 02, 2023 at 07:47:09 (EDT)

No Harm, Yes Foul

The "No Harm, No Foul" rule is simply wrong – as per the lovely anecdote told by wise investor-philosopher-professor Benjamin Graham ("Current Problems in Security Analysis", Lecture, New York Institute of Finance, 1947) quoted in the Hussman Funds Annual Report for 2023:

I recall to those of you who are bridge players the emphasis that bridge experts place on playing a hand right rather than on playing it successfully. Because, as you know, if you play it right you are going to make money and if you play it wrong you lose money – in the long run. There is a beautiful little story about the man who was the

weaker bridge player of the husband-and-wife team. It seems he bid a grand slam, and at the end he said very triumphantly to his wife "I saw you making faces at me all the time, but you notice I not only bid this grand slam but I made it. What can you say about that?"

And his wife replied very dourly, "If you had played it right you would have lost it."

(cf Lecture #10 of The Rediscovered Lectures of Benjamin Graham, and Capital Ideas (2000-04-08), Bubble Busters (2002-02-06), Harry Browne Rules of Financial Safety (2019-12-24), Shiller Price Earnings Ratio (2021-03-29), Irrational Exuberance (2021-08-13), ...) - ^z - 2023-10-02

- Monday, October 02, 2023 at 07:27:44 (EDT)

Jubilant Retirement

The word for "retirement" in Spanish is Jubilación – an obvious cognate for "jubilation", and the perfect term for an ideal transition from the Work-for-Pay-from-Others back to the Learn-and-Grow-for-Self early phases of Life!

(cf Bird's Nest on the Ground (2009-07-19), Bob Williams Sketch - Nearing Retirement (2011-07-21), Retirement News (2011-08-18), Bob Williams Sketch - Retirement Express (2011-10-04), Retirement Mental Health Advice (2023-05-25), and course notes parts [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], ...) - ^z - 2023-10-02

- Monday, October 02, 2023 at 07:04:21 (EDT)

Ways to Mend the World

Another kind, helpful, loving list to ponder, Anglican priest Tish Harrison Warren's "11 Small Ways You Can Help Mend the World", in her newsletter from the New York Times dated 12 June 2022:

- Have more in-person conversations. — "... interaction, however profound, however fleeting, helps us connect with others in ways that cannot be replicated online but that form the very fabric of our lives and society."

- Get outside. — "... We are made to be creatures who spend a lot of time in the natural world, and doing so humanizes us in deeply necessary ways."

- Eschew mobs – online and in real life. — "... when a protest or conversation becomes unruly and vicious, certainly if it skews toward violence, then it contributes more heat than light to the world."

- Read books. —"... the world is complex. In order to even attempt to understand it, we have to sit with slower, longer arguments, stories and ideas."

- Give money away. — "... the first question to ask in making a budget is, 'How can I use what I have to repair the world?'"

- Invest in institutions more than personal brands. — "... One way to rebuild a better world is to invest time, money and energy into reforming broken institutions and sustaining healthy ones."

- Invest in children. — "... If we want a flourishing future, we must seek the flourishing of children in the present."

- Observe the Sabbath. — "... We, as a people, need rest. One intentional way to find it is to use one day of seven to chill out. Don't work. Don't get on screens. Don't spend money, if you can avoid it. Enjoy the world or a nap. Slow down. ... allow those who work for us or around us to also embrace both meaningful work and rest."

- Make a steel man of others' arguments. — "... Choosing to seek out the best arguments of those with whom we disagree requires humility and curiosity, and it makes for healthier societal discourse."

- Practice patience. — "... 'Patience outfits faith, guides peace, assists love, equips humility, waits for penitence, seals confession, keeps the flesh in check, preserves the spirit, bridles the tongue, restrains the hands, tramples temptation underfoot, removes what causes us to stumble. ... It lightens the care of the poor, teaches moderation to the rich, lifts the burdens of the sick, delights the believer, welcomes the unbeliever. ... For where God is there is his progeny, patience. When God's Spirit descends patience is always at his side.' [Robert Louis Wilken]"

- Pray. — "... prayer and work go together. And because, ultimately, true renewal requires more than we can do on our own."

... yes, rather religious – and yes, full of hope and good ideas for the future.

(cf Inspiration Prayer (2003-04-10), Help, Thanks, Wow (2013-02-25), Mr Rogers Asks (2019-11-18), Clearly, Dearly, Nearly (2020-02-05), Mantra - Greater Love (2020-02-21), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-30

- Saturday, September 30, 2023 at 07:35:00 (EDT)

Friendship

"Being There" by David French (NYT Gift Link) is a beautiful ode to friendship – including:

... the first commandment of friendship:

presence.

Simply being there ... |

It concludes with the author's advice to some young people:

Stay together, I said. It's going to get hard. Your kids are young. Your careers are just starting to take off. But stay together. Be there, even when it's hard. Even when it's inconvenient. After I got off the call, I kicked myself for not remembering a quote by C.S. Lewis: "Friendship is unnecessary," he wrote, "like philosophy, like art, like the universe itself (for God did not need to create). It has no survival value; rather it is one of those things which give value to survival."

That single quote says so much. Compared with the competing demands of family and work, in any given moment friendship can feel unnecessary. But as the years roll on, and countless justifiable individual absences wear down our relationships, there will come a time when we will feel their loss. But it need not be that way, especially when our simplest and highest command is merely being there.

... and that's what friends do!

(cf Friendship and Meditation (2012-11-06), Stand by You (2017-01-11), Friend Sits by Friend (2018-07-04), Unconditional Friendliness (2018-08-10), What Friends Do (2019-11-26), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-28

- Thursday, September 28, 2023 at 08:58:59 (EDT)

Money and Happiness, Analyzed

"The Rich Are Not Who We Think They Are. And Happiness Is Not What We Think It Is, Either." by Seth Stephens-Davidowitz is a cute data-analytic 2022 book-excerpt. It begins by noting that most high-earning people – the top 0.1% who take in more than ~$1.5M/year – are not famous billionaires. They're owners of a "regional business" like an auto dealership or beverage distributor. These tend to be local quasi-monopolies that make money in a boring way.

More fascinating are Stephens-Davidowitz's comments on happiness and its sources. Getting more money helps, but only logarithmically. ("You need to keep doubling your income to get the same happiness boost.") The leading factors behind feeling good are unsurprising:

The activities that make people happiest include sex, exercise and gardening. People get a big happiness boost from being with a romantic partner or friends but not from other people, like colleagues, children or acquaintances. Weather plays only a small role in happiness, except that people get a hearty mood boost on extraordinary days, such as those above 75 degrees and sunny. People are consistently happier when they are out in nature, particularly near a body of water, particularly when the scenery is beautiful.

The data behind this are in the study "Are You Happy While You Work?" by Alex Bryson and George MacKerron. Its abstract summarizes:

Using a new data source permitting individuals to record their wellbeing via a smartphone, we explore within-person variance in individuals' wellbeing measured momentarily at random points in time. We find paid work is ranked lower than any of the other 39 activities individuals can report engaging in, with the exception of being sick in bed. Precisely how unhappy one is while working varies significantly with where you work; whether you are combining work with other activities; whether you are alone or with others; and the time of day or night you are working.

The results are in Table 3, "Happiness in Different Activities (fixed effects regression model)":

| Activity | % change in Happiness |

| Intimacy, making love | 14.20 |

| Theatre, dance, concert | 9.29 |

| Exhibition, museum, library | 8.77 |

| Sports, running, exercise | 8.12 |

| Gardening, allotment | 7.83 |

| Singing, performing | 6.95 |

| Talking, chatting, socialising | 6.38 |

| Birdwatching, nature watching | 6.28 |

| Walking, hiking | 6.18 |

| Hunting, fishing | 5.82 |

| Drinking alcohol | 5.73 |

| Hobbies, arts, crafts | 5.53 |

| Meditating, religious activities | 4.95 |

| Match, sporting event | 4.39 |

| Childcare, playing with children | 4.10 |

| Pet care, playing with pets | 3.63 |

| Listening to music | 3.56 |

| Other games, puzzles | 3.07 |

| Shopping, errands | 2.74 |

| Gambling, betting | 2.62 |

| Watching TV, film | 2.55 |

| Computer games, iPhone games | 2.39 |

| Eating, snacking | 2.38 |

| Cooking, preparing food | 2.14 |

| Drinking tea/coffee | 1.83 |

| Reading | 1.47 |

| Listening to speech/podcast | 1.41 |

| Washing, dressing, grooming | 1.18 |

| Sleeping, resting, relaxing | 1.08 |

| Smoking | 0.69 |

| Browsing the Internet | 0.59 |

| Texting, email, social media | 0.56 |

| Housework, chores, DIY | -0.65 |

| Travelling, commuting | -1.47 |

| In a meeting, seminar, class | -1.50 |

| Admin, finances, organising | -2.45 |

| Waiting, queueing | -3.51 |

| Care or help for adults | -4.30 |

| Working, studying | -5.43 |

| Sick in bed | -20.4 |

The comments for the above table observe:

In Table 3 we see how working compares to the correlations with other activities. The most pleasurable experience for individuals is love-making and intimacy, which raises individuals' happiness by roughly 14% (relative to not doing this activity). This is followed by leisure activities such as going to the theatre, going to a museum and playing sport. Paid work comes very close to the bottom of the happiness ranking. It is the second worst activity for happiness after being sick in bed, although being sick in bed has a much larger effect, reducing happiness scores by just over 20%.

Bottom lines:

- So sad to see how many people don't enjoy their Jobs!

- So surprising to see modern online media making so little difference!

- So sweet to see Nature, Art, Activity, and Connection at the top of the happy-making list!

(cf Optimist Creed (1999-04-16), Unenviable Happiness (2006-02-27), Pursuit of Happiness (2008-11-19), Models of Happiness (2012-01-05), Happiness Buffer (2013-12-22), Mantra - Happiness Is (2018-03-20), Happiness and Excellence (2021-11-10), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-26

- Tuesday, September 26, 2023 at 07:48:24 (EDT)

Abundance Mindset

Sonia Vadlamani's essay "Abundance mindset: why it’s important and 8 ways to create it" suggests a rich set of strategies to pursue toward happiness, prosperity, sharing, and hope:

- Believe in infinite possibilities

- Understand the power of your thoughts

- Stop comparing yourself to others

- Incorporate gratitude as a daily practice

- Build win-win situations for all

- Be willing to learn

- Create daily affirmations that encourage abundance

- Surround yourself with others with abundance mindset

(cf Incalculable Wealth (2000-11-12), Hopeful Rejoinders (2001-06-23), Millions of Good Deeds (2014-05-20), See the Good in Others (2018-01-02), Sharing Awareness (2020-07-06), Cup Full of Love (2021-08-02), Genuine, Gallant, Generous, Grateful, Good (2023-09-16), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-21

- Thursday, September 21, 2023 at 07:48:50 (EDT)

Eleven Laws of Systems Thinking

Suggestions from Peter Senge's book The Fifth Discipline:

- Today's problems come from yesterday's solutions.

- The harder you push, the harder the system pushes back.

- Behavior grows better before it grows worse.

- The easy way out leads back in.

- The cure can be worse than the disease.

- Faster is slower.

- Cause and effect are not always closely related in time and space.

- Small changes can produce big results – but the areas of highest leverage are often the least obvious.

- You can have your cake and eat it too – but not all at once.

- Dividing an elephant in half does not produce two small elephants.

- There is no blame.

(cf Transient Behavior (1999-05-11), Epistemological Enginerooms (2000-08-10), Fifth Disciplinarians (2000-09-10), Discussion and Dialogue (2006-01-07), Awareness, No Blame, Change (2009-04-19), Learningful Life (2021-07-02), Work as School (2023-06-02), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-20

- Wednesday, September 20, 2023 at 07:47:41 (EDT)

Stiff

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach (2003) is a humorous survey of dead bodies. The chapters cover a wide range of applications:

- medical school teaching and learning

- the history of body-snatching

- decay and decomposition

- crash test subjects

- post-accident forensics

- military experimentation

- crucifixion tests

- organ donation

- cannibalism

- cremation, composting, and other disposal methods

... and more! Roach's writing style is smooth and chatty; the technical content seems reliable; the only major fault is the lack of an index.

(cf Prayers of Comfort (2004-01-07), Johnson Condolences (2008-01-05), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-18

- Monday, September 18, 2023 at 14:02:15 (EDT)

Recovery to Health

From "The Checkup With Dr. Wen: Three lessons for people struggling with prolonged recovery", gentle-wise suggestions by Leana S Wen for those facing medical (or other!) challenges:

- Push for an answer, but know there might not be one. — Much of medicine exists in a gray area. Often, things are clear only in retrospect. A course of treatment can be a form of diagnosis. What works for one person might not work for another. Being an advocate for your care means bringing up concerns to your providers, but they, too, are limited in what they can do. That doesn't mean patients should give up. Keep a journal of how you feel in response to various treatments. Learn from online communities and proactively bring up options with your providers. You are the expert when it comes to your body; speak up when something isn't right and continue pushing to try methods that could help.

- Redefine your goals. — Goals need to be calibrated to your circumstances. If you’re facing setbacks from illness or other life events, it’s okay — indeed necessary — to set new objectives and take things day by day.

- Find joy and gratitude where you can.

All so difficult to do, and so important to try (or at least try to try) — even when not (totally) successful — and to Dr Wen's list, perhaps add:

(cf Optimist Creed (1999-04-16), Personal, Permanent, Pervasive (2009-04-27), Disease as Journey (2009-12-16), Tough-Minded Optimists (2009-12-22), Power of Optimism (2016-02-23), Sheryl Sandberg on the Hard Days (2016-05-22), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-18

- Monday, September 18, 2023 at 07:00:58 (EDT)

Longevity List

Obvious and important: observations in the article "4 things the world’s longest-living people—residents of ‘Blue Zones’ like Okinawa and Sardinia—do to stay healthy and happy" by Renée Onque (CNBC, 2023-09-16), citing Dan Buettner:

- Exercise — "They move naturally." — walking, gardening, and other frequent, low-intensity physical activities

- Optimism — "They have a positive outlook on life." — often via faith, purpose, or a "true calling"

- Diet — "They eat wisely." — in moderate amounts, of mostly plant-based foods

- Relationships — "They value connection." — with family, friends, community

... not a lot of rocket science, and not bad ideas to practice!

(cf Bennett on Life (2000-03-19), Life Time Management 1 (2001-06-13), Old Age (2007-05-22), Old Age Hardening (2012-06-07), Ikigai (2020-07-18), Awe Walk (2020-10-04), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-17

- Sunday, September 17, 2023 at 07:59:50 (EDT)

Genuine, Gallant, Generous, Grateful, Good

Turn around some common character woes – scared, selfish, spiteful, small – and make a list of positives, perhaps in an alliterative style to aid memory and encourage virtue?

- Genuine – fully present without pretense, an unclothed self

- Gallant – polite, helpful, courageous, noble

- Generous – kind in sharing wealth and blessings

- Grateful – feeling thanks, giving praise

... and of course:

(cf Smile and Listen (2011-08-20), Let Others Be Right (2012-12-31), The Heart of Buddhism (2015-01-10), See the Good in Others (2018-01-02), 2019-06-16 - Self-Discovery, Skills of Mind, Generosity of Heart (2019-07-07), Mantra - Give More Praise (2019-07-28), Being Simply Beautiful (2021-06-04), Gratefulation and Gratituding (2021-11-11), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-16

- Saturday, September 16, 2023 at 08:00:38 (EDT)

The Marriage Question

Clare Carlisle's book The Marriage Question: George Eliot's Double Life is a deeply detailed and insightful literary biography of Mary Anne Evans aka Marian Evans aka George Eliot (1819-1880), the extraordinary British novelist who "married" — but not in the eyes of the law or society — the love of her life, George Lewes. Carlisle's analysis of Eliot's maculate situation is fascinating and raises profound, important questions about life. As the book's synopsis says:

... Through the immense ambition and dark marriage plots of her novels, we see Eliot wrestling—in art and in life—with themes of desire and sacrifice, motherhood and creativity, trust and disillusion, destiny and chance. ...

And there are indeed so many questions, including:

- how (and how much) should social norms, civil or religious laws, and moral standards bind people to their marriage vows?

- what should a married couple do if one of them changes radically and is no longer the person they once (or never) were?

- must wives and husbands hide domestic suffering in their marriage from outsiders?

- can people within a marriage love others — and if so, how and how much?

Carlisle in her Preface touches upon such issues and their relevance today, more than a century later:

... how do you tell the difference between protectiveness and control, between love and selfishness, between loyalty and submission? Who has compromised more, sacrificed more, suffered more? Who has the most power? ... Many of the themes [Eliot] explores in her art — desire, dependence, trust, violence, sanctity — could be transferred to wider, less traditional ideas of married life. ... Eliot's unusual circumstances brought her closer to a modern experience of marriage. She was involved with several men before settling down with a long-term partner in her mid-thirties. She chose not to have children, and navigated relationships with Lewes's sons. Within a few years of her married life she was earning much more than her husband. Living at once inside marriage and outside its conventions, she could experience this form of life — so familiar yet also so perplexing — from both sides. A successful marriage was never, for this woman, an easy lapse into social conformity, but a precarious balancing act — and people were watching to see if she would fall.

Earlier in the preface, via rich metaphors, Carlisle sketches the reality of long-term relationships:

Marriage is made of these intimate and ephemeral moments, yet it also has epic proportions. It stretches out through time, into the future, growing and changing: that is why George Eliot had to write grand novels such as Middlemarch to bring it into view. Like a plant, a long-term relationship has its phases of development, its cycles, its seasons, its changing weather. Under adverse conditions, it might wither and die; it might come close to death and then revive. When we imagine a marriage like this, we think about how it is connected with other living things — other people, other relationships — and rooted in an ecosystem. Victorian philosophers learned to call this ecosystem a 'milieu' or 'environment'. We could also call it a world: a mixture of natural, social and cultural conditions.

Getting together with another person means stepping into their world: their family, friendships, culture, career path, ambitions; the places they know and the possibilities they contemplate; their taste and style and habits. Being in a marriage — legal or otherwise — means living in a shared world. We might even say that the marriage is this shared world: again, something that grows and changes.

... beautiful, thoughtful, provocative!

(cf My Religion (2000-11-06), Barrett and Browning (2001-11-11), Interracial Checkmate (2004-07-20), Painting vs Writing (2006-03-29), Love and Marriage (2007-08-01), Passage to India - Love and Marriage (2017-10-30), Hearing the Grass Grow (2020-02-08), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-12

PS And there's also arch humor, as in Chapter 11 ("The Other Shore") where Carlisle breaks the fourth wall in discussing Eliot's marriage, two years after Lewes death in 1878, to John Cross, 20 years younger than she:

When he reaches this part of the book, my editor is shocked. He has been filled with admiration for Eliot — so gifted, so brave, so thoughtful and profound — and now I am suggesting that she married John Cross so that he would write her biography and have her buried in Westminster Abbey. He does not like it at all. Why must we ascribe to her such mercenary motives? No!' I cry — it comes out louder than I meant it to — and explain that of course her reasons were mixed: she liked Cross, genuinely cared for him, probably fancied him too. My editor is still frowning. Usually I am rather in awe of him, but now I launch into a vehement speech. Why does anyone get married? people don't choose a partner just for their intrinsic qualities, but for the whole world they bring. Very often marriage promises some change for the better: an end to loneliness, alleviation of hardship, escape from parental control, the kudos of an attractive or successful spouse, a nicer home, a new social circle, the prospect of children, help with life's practicalities, creative inspiration . . . When a relationship seems to be reduced to such extrinsic motives, we are quick to judge it harshly. But this is not how I see Eliot's marriage to Cross at all! I pause for breath. 'So say all that! he says with a sweep of the hand, and of course I follow his advice.

While Romanticism bursts through conventional moral codes, it carries a moralism of its own — an urge to purify marriage of its self-interest, its worldliness, its pragmatism. I am sure that ambition, mixed with love and loneliness, provided Eliot with a motive for marrying Cross — just as a similar mixture had led her to choose Lewes. Like my editor, she disapproved of this particular motive, and devised a marriage plot that carefully concealed it.

Ha!

- Tuesday, September 12, 2023 at 19:09:52 (EDT)

Better Memory

So as not to forget 😊, some obvious-and-good suggestions from Jancee Dunn's NYT essay "Phone. Keys. Wallet … Brain?:

- limit multitasking

- reduce stress

- get adequate rest

- eat healthy

- exercise

(cf Parallel Processing Paradox (2004-09-24), Mediocre Multitaskers (2009-09-01), Mantra - Do Less, Better (2016-12-14), Memory Improvement (2022-07-10), ...) - '^z - 2023-09-12

- Tuesday, September 12, 2023 at 08:41:06 (EDT)

Don't Do Your Best

Memorable bits from Keith Johnstone's TEDx YYC talk "Don't Do Your Best (transcriber Midori T, reviewer Hiroko Kawano):

I always think teachers should reveal everything to their students, especially when they don't know something. All the teachers I ever had always knew something, which was really discouraging. They teach you that they choose really good poems, so then you think, 'I can never write one like that.' ...

... and

I decided when I was just before my ninth birthday not to believe anything the grown-ups said. And the next day, I decided to always see if the opposite could be true. I think it changed my life. I've been doing it ever since. And it taught me to be looking for the obvious and not the clever. The obvious is really your true self. The clever is an imitation of somebody else, really.

... and

The audience think inside the box. If the phone rings, they think you're going to answer it. The phone can ring on an improvisation stage, and somebody will hide behind the sofa because they're wanting to be original.

... and from the slides of quotes – of which only four of the eleven were used:

- I have spent my life in the pursuit of the obvious. — "I never said that!"

- Be average. — "That's right!"

- Those who say 'yes' are rewarded by the adventures they have. Those who say 'no' are rewarded by the safety they attain. — "I think that's self-explanatory."

- Striving after originality makes your work mediocre. — "Striving after originality is trying to think outside the box."

(cf Impro (2012-11-10), Yes, and... (2012-11-14), Positive and Obvious (2012-12-12), Status and Teaching (2012-12-19), Make Mistakes (2013-02-27), Check Your Partner (2013-03-30), Keith Johnstone Improv Quotes (2013-12-26), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-10

- Sunday, September 10, 2023 at 19:51:36 (EDT)

Electrolyte Friends

Funny how giving or receiving a tiny gift can lead to something marvelous! Three dear trail buddies, for instance, first met during ultramarathons a decade or more ago. One or the other of us was suffering from electrolyte imbalance, cramping up, or game-ending fatigue. A timely mid-course present of a few electrolyte capsules ("Succeed!" brand e-caps, as it turned out) solved the problems and laid the foundations for long-term friendships. The stories began at:

... and continued in dozens of runs, races, and other meetings thereafter. So wonderful we met, comrades!

^z - 2023-09-07

- Thursday, September 07, 2023 at 07:59:04 (EDT)

They Have a Word for It

Howard Rheingold's 1988 book They Have a Word for It is subtitled "A Lighthearted Lexicon of Untranslatable Words and Phrases". It's fun, albeit a bit dated in tone, not dense in information, and erratic in quality. Some of the better words are widely known already; others are deservedly forgotten. Here a few examples that may lie somewhere in between:

- gemütlich (German) — cozy, comfortable, genial, homey

- Zeitgeist (German, "spirit of the time") — the prevailing mood of a certain period

- saper vivere (Italian, "to know how to live") – to know how to handle people diplomatically

- confianza (Spanish) — unshakable, firm belief in someone

- esprit de l'escalier (French, "the spirit of the staircase") or Treppenwitz (German, "staircase wit") — clever remark that comes to mind when it is too late to utter it

- mantra (Sanskrit) — word or syllable uttered to oneself in order to achieve a state of mind; a linguistic mind-tool

- Torschlüsspanik (German, "door-shutting panic") — fear of being left out

- Drachenfutter (German, "dragon fodder") — a peace offering, a gift given out of guilt for having too much fun

- wabi (Japanese) — a flawed detail that creates an elegant whole

- sabi (Japanese) — beautiful patina

- aware (Japanese) — feelings engendered by ephemeral beauty

- shibui (Japanese) — beauty of aging

- bricoleur (French) — a person who constructs things by random messing around without following an explicit plan

- ponte (Italian) — an extra day off, taken to add a weekend to a national holiday

- lagniappe (French) — an unexpected gift to a stranger or customer

- Gedankenexperiment (German) — thought-experiment

- Weltschmertz (German, "world grief") — a gloomy, romanticized, world-weary sadness

- Schadenfreude (German) — joy that one feels as a result of someone else's misfortune

- mu (Japanese) — a Zen term for No-thing or no-mind

- tao or dao (Chinese) — the Way

- tikkun olam (Hebrew) — spiritual and political reformation of the world

- Gestalten (German) — little wholes that make up larger wholes

- Zwischenraum (German) — the space between things

Many of Rheingold's words are ostentatiously obscure, arcane, or of questionable utility. May they rest in piece, along with their forgotten siblings!

(cf Weekend Bridge (2014-04-16), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-06

- Wednesday, September 06, 2023 at 21:42:08 (EDT)

Burnout

The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives, by Jonathan Malesic is, sadly, a mostly-personal report on the author's tragic life-experiences, clothed in a discussion of historical-societal exhaustion, depression, and general suffering associated with "work". There are insightful bits – esp perhaps the discussion of "workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values" as six key areas (identified by Michael Leiter and Christina Maslach). As Malesic summarizes near the end of Chapter 4:

... Workload and reward represent what you put into work and what you get in return. The relation between them is a question of justice, of getting what you deserve. Fairness is also about justice. Autonomy is indispensable to moral responsibility and action. Community is the human context for our ethical actions and the source of our moral norms. And values inform all aspects of our moral lives.

Justice, autonomy, community, values: these are the basic components of ethics. And when they are damaged or absent in a workplace, employees are likely to feel drawn across a widening gap between their ideals and the reality of their jobs. They're more likely to become exhausted and cynical and lose their sense of accomplishment. This means burnout is fundamentally a failure of how we treat each other; it's a failure of ethics, the norms of action within our culture. People burn out because, in our organizations, we do not afford them the conditions they desire or deserve.

Excellent insights! But overall, Burnout is long on anecdote and short on higher-level analysis. Malesic includes appropriate disclaimers, like "... I am just one worker; I want to be careful not to overdraw any conclusions about work itself from experience that may be peculiar to me. ...". And Malesic's vision is a noble one, as he summarizes in Chapter 6:

To overcome burnout, we have to get rid of that ideal and create a new shared vision of how work fits into a life well lived. That vision will replace the work ethic’s old, discredited promise. It will make dignity universal, not contingent on paid labor. It will put compassion for self and others ahead of productivity. And it will affirm that we find our highest purpose in leisure, not work. We will realize this vision in community and preserve it through common disciplines that keep work in its place. The vision, assembled from new and old ideas alike, will be the basis of a new culture, one that leaves burnout behind.

The vision, however, is far better captured in his op-ed essays in the NY Times, parts of which are derived from Burnout.

(cf Future of Work (2021-09-26), Not Your Job (2023-09-04), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-06

- Wednesday, September 06, 2023 at 14:07:54 (EDT)

Not Your Job

Jonathan Malesic in his NYT op-ed "College Students: School Is Not Your Job" offers a deep insight on work versus being and learning and growing and flourishing:

College is a unique time in your life to discover just how much your mind can do. Capacities like an ear for poetry, a grasp of geometry or a keen moral imagination may not ‘pay off’ financially (though you never know), but they are part of who you are. That makes them worth cultivating. Doing so requires a community of teachers and fellow learners. Above all, it requires time: time to allow your mind to branch out, grow and blossom.

... and openness to new learning applies to old retirees too! – and everyone else, eh?

(cf Pursuit of Excellence (2002-02-22), Knowledge and Society (2002-03-25), Improving My Mind (2003-06-22), What We Know (2006-08-15), Asimov on Libraries (2007-12-28), Learn to Learn (2020-01-29), Learningful Life (2021-07-02), Future of Work (2021-09-26), Work as School (2023-06-02), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-04

- Monday, September 04, 2023 at 21:20:25 (EDT)

Proud Hugs

Public embraces:

... in the gas station driveway

— as if we were newlyweds

... at the metro parking lot

— as if it were time to part forever

... beside the giant MRI magnet

— as if someone were about to enter surgery

... next to the table in the restaurant after dinner

— as if this were the last meal before an execution

Or maybe ... we're just sharing our loving friendship with the World!

(cf Startled by Beauty (2002-12-31), Silver Anniversary (2003-09-06), Public Glimpses (2007-03-10), In a Poem (2010-06-17), Elements (2015-06-02), Startled by Beauty (2016-11-17), Be the Loving (2018-06-03), In Your Eyes (2018-08-04), Imagine Meaningless Beauty (2018-11-09), Like a Bud (2020-03-21), Like a Hand, Like a Wind (2021-04-26), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-04

- Monday, September 04, 2023 at 15:48:35 (EDT)

Goodnight Mind for Teens

Books on how to reduce insomnia are many and diverse. Goodnight Mind for Teens: Skills to Help You Quiet Noisy Thoughts and Get the Sleep You Need by Colleen Carney focuses on helping adolescents get better sleep via science, mindfulness, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) methods. It's fast-reading and — maybe, for some people who follow its suggestions for a few months — could be helpful. The ten "tips" are actually a good high-level outline of the approach:

- Identify Your Sleep Problem with the Right Tool: The Sleep Tracker

- Use Your Body Clock to Get Better Sleep and Feel Better During the Day

- Wind Down Before Bed

- Make a Plan for Managing Anxiety

- Stay Awake During the Day by Addressing Sleepiness

- Develop a Plan for Getting Out of Bed in the Morning

- Develop a Plan to Feel More Alert During the Day

- Manage Substances That Rob You of Deep Sleep

- Think Like a Good Sleeper

- Make a New Plan If Your Sleep Remains a Problem

... good steps for problem-solving in general!

^z - 2023-09-03

- Sunday, September 03, 2023 at 15:25:01 (EDT)

Lost Art of Reading Nature's Signs

Tristan Gooley's book The Lost Art of Reading Nature's Signs has the enchanting subtitle "Use outdoor clues to: find your way; predict the weather; locate water; track animals; and other forgotten skills". And it really does deliver on those promises!

Lost Art isn't summarizable – it's a semi-organized buffet of observations, methods, phenomena, rules, and connections. The main focus is mindful walking – paying attention and asking oneself questions about what one is sensing. Gooley explores Earth and sky, plants and animals, natural and artificial structures, and the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars. There are also safety tips, personal stories, and silly cynical asides. For instance, from the Introduction:

Most of the walking books I have come across over the years get bogged down in obsessive attention to safety and equipment. I have rarely found myself enjoying these books, because I do not go walking with the purpose of staying within a world of perfect safety and comfort. Personally, I would rather die walking than die of boredom reading about how to walk safely. This is a theory I have experimented with over the years, as you will see.

In this book I will take the original approach of assuming that you are capable of walking safely and with roughly the right socks on. If you are the sort of person who likes to go ice-climbing in a nightie, then you probably don't read many walking books and I suspect it would take more than a book to mend your ways. With a handful of exceptions, my advice in the area of safety is three words long: don't be daft.

That said, everyone needs the right tools for certain jobs.

The Introduction concludes with a fine Executive Summary of the whole mission:

This is a book about outdoor clues and signs and the art of making predictions and deductions. The aim of the book is to make your walks, however long or short, eminently more fascinating. I hope you enjoy it.

A smörgåsbord of delight follows ...

(cf Weltschmertz Rx (2005-07-13), Seeing Nature (2005-07-19), Miracles and Wonders (2007-03-31), Mantra - Keep Looking (2017-05-30), ...) - ^z - 2023-09-03

- Sunday, September 03, 2023 at 08:13:09 (EDT)